This Changes Everything

Naomi Klein | Personalist Politics in the White House and the C Suite | Factoids | Elsewhere

The three policy pillars of the neoliberal age — privatization of the public sphere, deregulation of the corporate sector, and the lowering of income and corporate taxes, paid for with cuts to public spending — are each incompatible with many of the actions we must take to bring our emissions to safe levels. And together these pillars form an ideological wall that has blocked a serious response to climate change for decades.

| Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything

…

Watching footage of the wildfires consuming large parts of L.A. — and texting with loved ones and friends living there — I couldn’t help wondering if this was the one, final tipping point that could galvanize a real move onto the war footing we need to combat — and overcome — climate change.

But then I recalled Klein’s three pillars, and considered Trump’s second term agenda. He’s stated his plans on all three pillars, so, if he continues on as he’s outlined, it’s highly unlikely that his administration will realign around countering climate change. Indeed, he continues to claim climate change is a hoax, and his allies state that the LA fires can be laid at the feet of Blue State policies, like DEI, not a warming world. (More on Trump in the following section.)

…

Related: see The Best Time to Fireproof Los Angeles Was Yesterday, by David Wallace-Wells, and some comments I made on Bluesky.

Personalist Politics in the White House and the C Suite

In an interview by Ezra Klein, political scientist Erica Frantz declared ‘America is undergoing a regime change. We think of that term as describing a change in who is in power, but I mean it in the sense of the political system itself — the way that power works.'

Trump's second term will dispense with ‘programmatic political parties’, the slow-moving, culture-bound political parties defined by processes, traditions, and — most importantly — by ideological adherence to policy positions. Instead, we are lurching to ‘personalist politics’ which is more like the court politics of monarchy, than what we usually think of as the American norm for political organizations.

Instead of political elites ‘caring about the long-term reputation of the party’, Frantz says that in personalist parties, ‘instead, we see elites really fearful of falling out of favor with the leader. So it’s a very different institutional dynamic.'

Basically, Frantz describes a hub-and-spoke model, where all the political elite have personalized relationships with the leader, who is involved in every major activity of the political party. She spells how deeply that goes. Consider, as one example, how Trump has come to play such a major role in the endorsement of candidates for elected office: go against Trump’s wishes, and you’ll be primaried. That has not been the case with Democratic or Republican presidents, at least for recent decades.

Frantz points out the hollowness at the core of personalism: The elite have caved, and no longer work together to find the best path to reach long-term policy goals. They have yielded all of that to the whims of the Leader. ‘The fundamental problem with these personalist leaders is that there’s no predictability in terms of what they might choose to pursue. And oftentimes, they make bad choices.' The leaders have closed off any internal dicourse about what is the best decision: those remaining will accede to whatever the leader wants.

What if ‘Founder Mode’ is really just personalism in corporate governance?

Venture capitalist Paul Graham is considered the first to name a particular style of corporate management ‘Founder Mode’, although he attributes the idea to a presentation by Brian Chesky, the CEO and founder of Airbnb.

In essence, although Graham never actually defines ‘Founder Mode’, he does lay out the pattern, which is like the hero’s tale: the founder is told that he needs to follow a certain path to scale the business, but that leads to poor results, and so the founder returns to how he did it at the start, as the founder. As Graham writes,

The theme of Brian's talk was that the conventional wisdom about how to run larger companies is mistaken. As Airbnb grew, well-meaning people advised him that he had to run the company in a certain way for it to scale. Their advice could be optimistically summarized as "hire good people and give them room to do their jobs." He followed this advice and the results were disastrous. So he had to figure out a better way on his own, which he did partly by studying how Steve Jobs ran Apple. So far it seems to be working. Airbnb's free cash flow margin is now among the best in Silicon Valley.

The audience at this event included a lot of the most successful founders we've funded, and one after another said that the same thing had happened to them. They'd been given the same advice about how to run their companies as they grew, but instead of helping their companies, it had damaged them.

Graham sidesteps the question of whether these founders a/ hired the right people (Frantz points out that personalists have a history of hiring friends and family who lack the skills or depth of experience for their roles), or b/ have the depth of experience to deal with leading a team of experienced managers, which takes a great deal of expertise. A 30 year-old founder with little or no time spent in larger firms might be operating at a disadvantage in a company experiencing rapid growth. (And Graham doesn’t touch on how unsuccessful founders managed their companies.)

He describes the dilemma of such founders this way:

In effect there are two different ways to run a company: founder mode and manager mode.

Only two? What about worker-owned cooperatives? What about heavily unionized industries? Or maybe he's saying that there are two ways to run a high tech startup?

Till now most people even in Silicon Valley have implicitly assumed that scaling a startup meant switching to manager mode. But we can infer the existence of another mode from the dismay of founders who've tried it, and the success of their attempts to escape from it.

And ‘Manager Mode’ means something like this:

The way managers are taught to run companies seems to be like modular design in the sense that you treat subtrees of the org chart as black boxes.

The 'subtrees' are individuals, but viewed as 'black boxes' out of which emerge decisions, and results. No discussion of how the people in the 'subtrees' might coordinate with each other. It's a wheel and spoke notion, with 'the founder' connected to the heads of the 'subtrees' who are each supposed to accomplish some subset of the founder's goals. It’s not how successful large companies run, really.

You tell your direct reports what to do, and it's up to them to figure out how.

You, a founder, tell non-founders/managers — lets call them flounders — what to do and they figure out how. Is there only one founder and all the rest are flounders?

But you don't get involved in the details of what they do. That would be micromanaging them, which is bad.

The 'which is bad' comment is a dig, pushing back on the 'wokeness' of democracy at work. 'Mustn't micromanage!'

Then, however, after anecdotes about Steve Jobs, Graham shifts gears and tries another walk through the Founder dilemma:

Obviously founders can't keep running a 2000 person company the way they ran it when it had 20. There's going to have to be some amount of delegation.

Reluctantly admitting the need for some degree of managerialism?

Where the borders of autonomy end up, and how sharp they are, will probably vary from company to company. They'll even vary from time to time within the same company, as managers earn trust.

Again, so much like personalism: flounders are put into a role by the leader/founder, and if they do what they are told the founder may start to trust them, and they are granted some small degree of autonomy. Unsaid: if they don’t, they are probably shown the door. I bet Founder Mode companies — like the elite ranks for Personalist governments — have high turnover.

So founder mode will be more complicated than manager mode. But it will also work better. We already know that from the examples of individual founders groping their way toward it.

Wait. After claiming that there are no books about it, and that it’s not been researched deeply, still we know it will work better than all other ways of managing?

I’m not sure we can gain much more by textual analysis of Paul Graham’s paean to founders. Let’s just look at one.

Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Meta.

In recent weeks, Zuckerberg has pivoted in a number of ways, with all the earmarks of a massive company being run like a Personalist government. Of course, he’s doing so in sympathetic vibration with the incoming Trump royal court, which he’s bent the knee to.

Because of the voting structure of Meta, Zuckerberg has effectively sole control of the company’s destiny, so he can unilaterally decide — presumably to make Trump happy — to drop fact checking, and to allow all sorts of what experts would consider hate speech to appear on the various Meta platforms. Some examples of what are allowed, now.

"There's no such thing as trans children."

"God created two genders, 'transgender' people are not a real thing."

"This whole nonbinary thing is made up. Those people don't exist, they're just in need of some therapy."

"A trans woman isn't a woman, it's a pathetic confused man."

But leaving his pandering aside (MAGA people want to dis transgender people), Zuckerberg has made some huge gambles that haven’t panned out, exactly the sort of big missteps that Frantz says personalist governments make because they lack the ingredients for good decision making. Zuckerberg squandered over $50B on the Metaverse, and his newest social app, Threads, probably cost billions to build, market, and launch. Its sizzle is gone:

Threads, a direct competitor of Elon Musk’s Twitter, had a formidable start, attracting more than 100 million users within just a week of launch. But as the initial excitement fizzles out, most people who’d signed up stopped using the app. According to data from market intelligence firm Sensor Tower, the number of daily active users on Threads fell 50 percent one week after a July 7 peak and was down 70 percent two weeks after the peak.

Zuckerberg, who owns Facebook, Instagram, and Whatsapp, attempted to steal users from Twitter, but looks like it’s not growing, with 275M users but only 33M daily users. It looks like another failed strategic push by Meta, like the Metaverse.

Meta relaxation of controls on discourse may attract some MAGA folks back, but is likely leading to the departure of more liberal users.

Personalism in business.

Elizabeth Anderson offered up the insight that businesses are private governments, formed and managed around the nominally neutral objective of making profits for the shareholders, while providing wages and benefits for employees and products for customers. However, the reality is far from that apparently benign fable, as she makes clear:

In the rich democracies of Europe and North America, the postwar period was distinguished by high rates of economic growth widely shared across economic classes, strong labor unions, a robust welfare state centered on universal social insurance, state investment in education and healthcare, powerful liberal-democratic institutions, and a general sense of optimism.

Today, the denizens of Europe and North America are suffering reversals of these developments. Neoliberal policies are largely to blame. Financialization, fiscal austerity, tax cuts for the rich, harsh welfare restrictions, assaults on labor unions, and international trade agreements favor capital interests and constrain democratic governance. These policies have increased economic inequality, undermined democracy, and reduced the state’s ability to respond to the needs and interests of ordinary people.

In my new book, Hijacked, I argue that neoliberalism revives the conservative work ethic, which tells workers that they owe their employers relentless toil and unquestioning obedience. It tells employers that they have exclusive rights to govern their employees and organize work for maximum profit. And it tells the state to entrench the authority of these executives through laws that treat labor as nothing more than a commodity. To reinforce the commodification of labor, the conservative work ethic instructs the state to minimize workers’ access to subsistence from sources other than wage labor, including publicly provided goods, social insurance, and welfare benefits.

With Trump as the leader of the new MAGA regime, corporate leaders will find resonance in making companies more authoritarian, and adopting what will likely be more personalist governance in the C Suite.

We can expect Trump policies will harden the tendencies of that ‘conservative work ethic’ and make private governments in business more personalist.

My bet is that personalism in the White House will be bad for the country, and personalism (‘Founder Mode’) will lead to less democracy at work, too.

Factoids

Dementia from car noise.

In Denmark, a multiyear study of 2 million people aged 60 and over found that fully 11% of dementia diagnoses could be attributed to roadway noise.

…

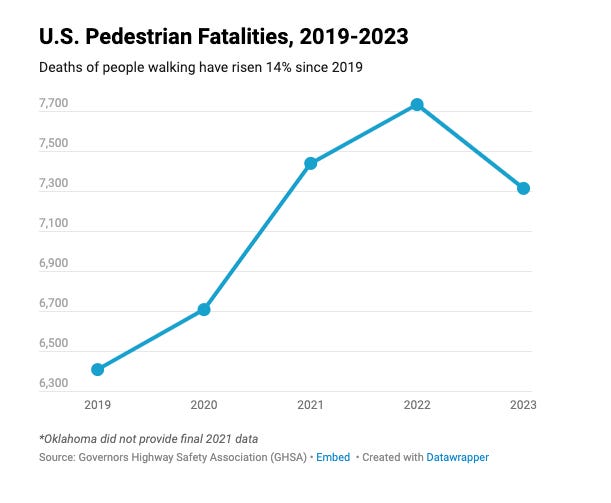

Pedstrian traffic fatalities up 77% from 2010.

GHSA's data analysis, Pedestrian Traffic Fatalities by State: 2023 Preliminary Data (January-December), projects that drivers struck and killed 7,318 people walking in 2023 – down 5.4% from the year before but 14.1% above 2019, the last pre-pandemic year.

| Governors Traffic Safety Association which notes 'Since 2010, pedestrian deaths have increased by 77%, compared to a 22% rise in all other traffic fatalities.' They link this to enforcement "A steep drop in traffic enforcement across the country since 2020 has enabled dangerous driving behaviors"‘

Cops not doing their jobs has a high cost.

…

Customers don’t trust the companies whose products they buy.

[A] cross-partisan rise in distrust has caught countless leaders and executives off guard. This year, PricewaterhouseCoopers surveyed business executives and found 90 percent of them thought customers trusted them a lot, while only 30 percent of customers surveyed agreed.

| Kristen Soltis Anderson, who continues: ‘In my work discussing public opinion surveys with executives, I am always struck by the number of successful leaders who are surprised that more Americans do not give them or their industry the benefit of the doubt or see the good in what they are doing. Regardless of intentions, the reality is that we are in a low-trust moment, and it binds right and left together.’

Positioning shared distrust in our institutions as a sign of unity is a bit much, Kristen.

Elsewhere

Using AI tools diminish critical thinking skills.

Michael Gerfich shares bad outcomes from using AI tools,

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work Futures to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.