More Like A Brain Than An Army

Stowe Boyd | Take the kids off the leash. | Looks like a bad trend for innovation. | What Will a Corporation Look Like in 2050?

In the year 2050, businesses in Humania are egalitarian, fast-and-loose, and porous. Egalitarian in the sense that Humania workers have great autonomy: They can choose who they want to work with and for, as well as which initiatives or projects they’d like to work on.

They’re fast-and-loose in that they are organized to be agile and lean, and in order to do so, the social ties in businesses are much looser than in the 2010s. It was those rigid relationships — for example, the one between a manager and her direct reports — that, when repeated across layers of a hierarchical organization, lead to slow-and-tight company.

Instead of a pyramid, Humania’s companies are heterarchies: They are more like a brain than an army. In the brain — and in fast-and-loose companies — different sorts of connections and groupings of connected elements can form. There is no single way to organize. People can choose the sort of relationships that most make sense.

| Stowe Boyd, What Will a Corporation Look Like in 2050?

An extract from an article I was commissioned to create that was published in 2015. Ten years later I pretty happy with how it has held up.

Humania is one scenario — the most hopeful one — in the article. Note that getting to that future requires a revolution — both a civil and a political revolution — that I call the Human Spring: ‘New populist movements rose up and rejected the status quo, and demanded fundamental change. At first the demands were uneven — some groups emphasized climate, or inequality, or the right to work. But by the mid 2030s, all three forces were more-or-less equal planks in the Humania platform.’

Without that revolution we don’t see that sort of business model — egalitarian, fast-and-loose, and porous — arise.

It feels like it’s time for the Human Spring, because our institutions are failing us on at least those three dimensions: climate, inequality, and the right to work, and it’s rapidly getting worse.

…

Here’s another extract from that piece regarding the right to work:

The central question of 2025 will be: What are people for in a world that does not need their labor, and where only a minority are needed to guide the ‘bot-based economy?

…

The full article is available for paid subscribers below the paywall.

If you become a paid subscriber and help ensure I can keep doing this work, you will get even more.

Short Takes

Take the kids off the leash.

In Giving Kids Some Autonomy Has Surprising Results, Jenny Anderson, Rebecca Winthrop summarize a growing body of research on the benefits of great autonomy for kids.

In a survey by Gallup and the Walton Family Foundation of more than 4,000 members of Gen Z, 49 percent of respondents said they did not feel prepared for the future. Employers complain that young hires lack initiative, communication skills, problem-solving abilities and resilience.

The authors talk about some of their own research:

Many recent graduates aren’t able to set targets, take initiative, figure things out and deal with setbacks — because in school and at home they were too rarely afforded any agency.

Giving kids agency doesn’t mean letting them do whatever they want. It doesn’t mean lowering expectations, turning education into entertainment or allowing children to choose their own adventure. It means requiring them to identify and pursue some of their own goals, helping them build strategies to reach those goals, assessing their progress and guiding them to course-correct when they fall short.

This approach works because it teaches kids strategies they’ll need to succeed in work and life — and keeps them invested, too. But a survey of over 66,000 young people that we conducted with the Brookings Institution and the education nonprofit Transcend showed that very few middle and high school students regularly have the opportunity to work this way. Only 33 percent of 10th graders report that they get to develop their own ideas in school. The result? In third grade, 74 percent of kids say they love school. By 10th grade, it’s 26 percent. School feels like prison, many teenagers told us over three years of research. The more time they spend in school, the less they feel like the author of their own lives, so why even try?

The proof that increased agency/autonomy helps? Research by Johnmarshall Reeve:

In 35 randomized control trials in 18 countries, he and other researchers found that when students are allowed some opportunity to take their own initiative, they are more engaged in class and better able to master new skills, they have better grades and fewer problems with peers — and they are happier, too.

How?

Reeve showed teachers how to use a reasoning tone.

Controlling language shuts students down.

When parents allowed their kids less agency, using “do this now” language and monitoring their progress closely, they did not learn as well.

Aliza Pressman offers: “Let kids do for themselves what they can already do. And guide and encourage them to do things they can almost do. And then teach and model for them the things that they can’t do.”

Seems to me this is what managers should do at work, too.

…

…

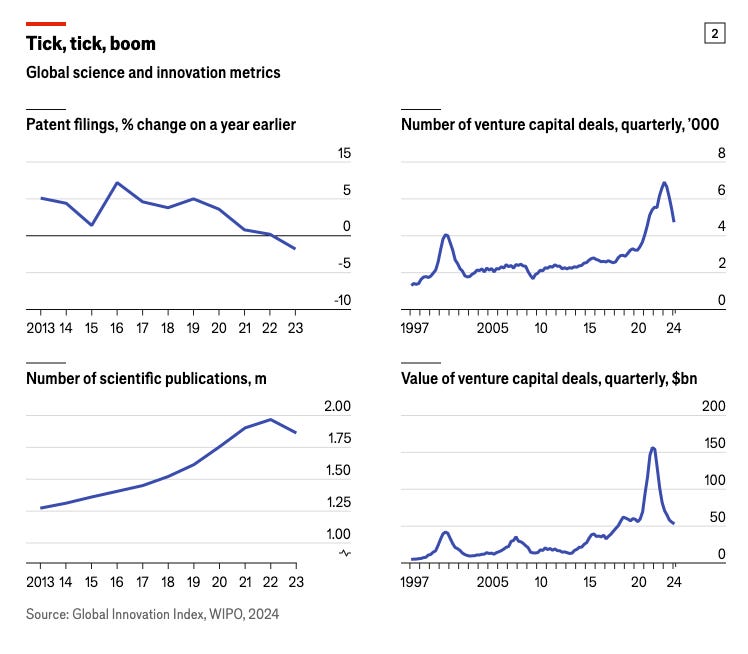

Looks like a bad trend for innovation.

Innovation boom is over? Post-pandemic slump?

What Will a Corporation Look Like in 2050? | Stowe Boyd

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work Futures to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.