Layers of Time: Pace Layers of Work

I have transposed Stewart Brand’s Pace Layers into the context of business.

Buildings aren’t made out of glass, concrete and stone: they’re made out of time, layers of time. | Frank Duffy

…

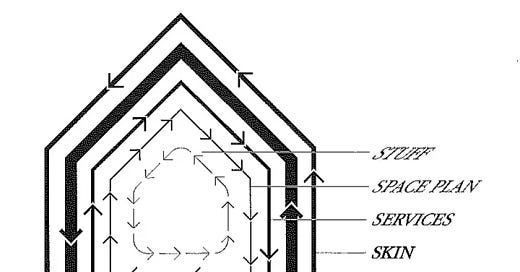

Stewart Brand was influenced by architect Frank Duffy’s ideas about architecture, leading to his book, How Buildings Learn, in which he created this diagram:

The thicker the arrows, the slower the change. This sets the stage for my essay, below.

In the first essay in this series on Layers of Time, I focused on the time distortion that the pandemic has caused, unsettling our perception of the pace of time. Even when we are not caught up in a pandemic, we are shifting from different scales of time, perhaps several times a day. However, we have become so enmeshed in this reality, that we may not even be aware of it, like fish who do not ‘see’ the water they are swimming in.

Work is a large presence in our lives, and it surrounds and buoys us, and we are subject to the many layers of time shifting all around us.

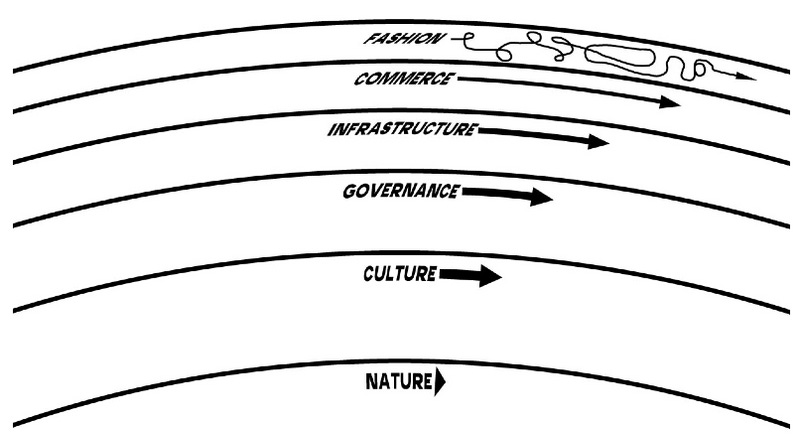

The brilliant Stewart Brand, along with musician and polymath Brian Eno, explored a model — Pace Layers — in which various elements of civilization are arrayed from fastest to slowest. (Note that he was inspired by the thinking of Frank Duffy, as seen in the opening quotation.)

As Brand’s original caption reads,

The order of a healthy civilization. The fast layers innovate; the slow layers stabilize. The whole combines learning with continuity.

He goes on in his description

In a durable society, each level is allowed to operate at its own pace, safely sustained by the slower levels below and kept invigorated by the livelier levels above. "Every form of civilization is a wise equilibrium between firm substructure and soaring liberty," wrote the historian Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy. Each layer must respect the different pace of the others. If commerce, for example, is allowed by governance and culture to push nature at a commercial pace, then all-supporting natural forests, fisheries, and aquifers will be lost. If governance is changed suddenly instead of gradually, you get the catastrophic French and Russian revolutions. In the Soviet Union, governance tried to ignore the constraints of culture and nature while forcing a five-year-plan infrastructure pace on commerce and art. Thus cutting itself off from both support and innovation, it was doomed.

So, the various layers have their own pace: fast at the top, slow at the bottom. Along with pace, they have differential levels of power and inertia. Fashion has a lesser impact on commerce than governance has on culture, and so on. But more importantly, since we are talking about social phenomena, these relationships have societal impacts:

Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous. Fast and small instructs slow and big by accrued innovation and by occasional revolution. Slow and big controls small and fast by constraint and constancy. Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power.

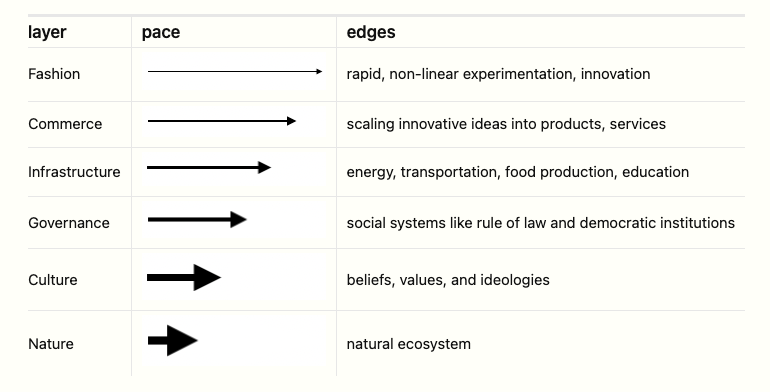

Rendered in a tabular form we get this, characterizing what is happening in the various layers. Note that the length and weight of the various layers represent speed and power, respectively.

A business is much like a civilization, I argue. And so I have transposed Brand’s Pace Layers into the context of business. I have included the terms ‘me-time’ and ‘we-time’ from Fighting for Time and True Asynch, where they are synonyms for ‘individual deep work’ and ‘group cooperative work’, respectively.

Note: I added a column to the table, adding a distinction between the inward-centered and the outward focuses of each layer.

Me-time — the work of the individual — is the combination of heads-down work and active learning. This, I argue, is the source of much of the innovation in business: someone has an idea, and shares it through connection with others, which imparts an influence on the next layer down, the group (we-time) layer.

Groups employ forms of communication, coordination, and cooperation, taking innovative starting points and combining them into new — or improved — products, processes, and patterns. Or, the group may reject the innovation, and remain as before. (This is a meta-pattern: the inertia of a lower layer can always deflect the activities of a higher layer. Fads come and go, many ideas die before implementation. This is the way the world works.)

These group activities can alter or exploit infrastructure to distribute new ideas across the organization. (Or reject them.)

sponsor: hal9

Chat with your enterprise databases using secure generative AI and empower business users in your team to do their own data analyses in seconds.

In turn, as these innovations are tried and tested, new forms or features of governance arise, which can influence the business’s culture, over time. Just so, ideas and innovations can spread from a single business to the greater marketplace. But at every interface, slow has the power, while fast gets the attention.

It’s clear that business culture changes quite slowly, and this model offers a means to understand why. It is reported that as much as 80% of change initiatives fail. To succeed, some group has to formulate a change plan, and then push down through the pace layers of work, fighting the inherent (and inescapable) inertia of each deeper level. This requires ongoing and constantly renewed pushing, where individuals have to convince groups to buy in, groups to build corresponding infrastructure, for governance models to adapt to new ways of doing things, and causing widespread shifts in cultural beliefs.

No wonder it is so hard. I’m surprised that 20% succeed, candidly.

But this is not just a model for how individual ideas percolate downward into the foundations of the business, it also shows how organizations exert force on those who make up the workforce. A deeply-seated cultural norm — a tendency to reward overwork, for example — that may have been inculcated by the company’s founder decades ago and found its way into all the layers above. So, when a new CEO comes aboard and wants to decrease high degrees of damaging burnout, she may have a yearslong campaign ahead of her, since workers across the company have internalized the ethical system of overwork, deeply, and it influences hiring, promotion, planning, and everything else it touches.

The most important takeaway is the insight that a ‘wise equilibrium between firm substructure and soaring liberty’ requires each layer to ‘respect the different pace of the others’, or else the civilization — or business — may collapse. And collapse can come from friction at any interface.

A civilization whose culture pushes too hard on nature? Ecological disaster. Or a business where leadership (its governance layer) does not adapt to organizational demands for change may find a large number of workers finding other work, as in the case of the return-to-office backlash.

In the third in this series, I will explore the relationships between layers of time and our place in it and the links between using time and finding meaning and purpose. And, yes, our sense of time is central to our sense of meaning and purpose.

Originally published on Sunsama.