In The Face of Contrary Facts

Hannah Arendt | The Right To Have Rights | Factoids | Elsewhere

Totalitarianism will not be satisfied to assert, in the face of contrary facts, that unemployment does not exist; it will abolish unemployment benefits as part of its propaganda.

| Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism

Brace yourself.

The Right To Have Rights

Reading Nico Grant’s recent article on ‘Perks Culture’ in the tech industry — and its apparent decline — led to one of the factoids in today’s issue: ‘The tech industry laid off more than 264,000 employees last year (2023), 100,000 more than the year before’.

Why is this happening? I’ve seen a lot of explanations, most focused on a litany of economic pressures hitting tech companies:

inflation hit the economy and led to higher interest rates so tech companies found money harder to get or more expensive;

the tech sector overhired during the pandemic, and found itself overstaffed for a cooling economy;

fears of recession (which never materialized) led companies to downsize preëmpively;

AI, some say, is already having an impact in the tech sector, allowing companies to make cuts with the same output afterward;

companies may be outsourcing and offshoring work, leading to head count reductions in the office, while paying substantially less for work done by freelancers or overseas workers.

Hardly anywhere do I see a more nefarious storyline. Namely, is it possible that these companies are colluding — directly or obliquely — to cull hundreds of thousands of workers to shift the power balance to the benefit of the tech behemoths? Over the past decade, increasingly activist workers created unions, protested corporate policies and working with governments on questionable security and defense projects, and adopted informal work slowdown practices like quiet-quitting. And of course the biggest headache is the tech workforce wanted to continue remote work — or at the least hybrid work — for all the obvious benefits.

The companies, from their perspective, had every reason to counter these efforts by workers to gain a larger influence on business direction.

Remember, these are the same companies that formerly colluded to avoid poaching employees from each other, illegally, and coordinated on the use of non-competes to minimize worker independence.

Fighting against remote work is actually counter to the direct business interests of the companies, as has been demonstrated by much research. For instance, In Return to Office Mandates and Brain Drain, Yuye Ding and colleagues spell out the negatives of RTO efforts [emphasis mine]:

In this paper, we empirically examine the effect of return-to-office mandates on employee turnover and hiring, using a sample of 54 high-tech and financial firms in the S&P 500 index. We find that these RTO firms experience higher employee turnover rates after announcing RTO mandates. Our findings validate the concern that RTO mandates may induce employees to leave for other firms and are consistent with the overwhelmingly negative employee response. We further find that female employees, more senior employees, and employees with higher skill levels are more likely to leave RTO firms, consistent with RTO firms losing highly valuable employees. Finally, we find that it takes longer for RTO firms to fill new job positions. These firms also hire fewer employees following the RTO mandates. Together, our evidence suggests that RTO mandates are costly to firms and have serious negative effects on the workforce. These turnovers could potentially have short-term and long-term effects on operation, innovation, employee morale, and organizational culture.

So, perhaps the ‘negatives’ are the point? Both the layoffs and the brain drain from RTO mandates lead to a huge pool of tech workers out of work, off the profit-and-loss statement, and decreasing worker power since most of those affected are scrambling to find new jobs. Meanwhile, the companies have shaken the tree and gotten rid of troublemakers, quiet quitters, those with children or aging parents detracting from long hours at work, along with the most highly-paid senior employees. Such companies are fine with longer times to find new employees — they can be very aggressive in hiring the best at the lowest price. They can cut perks with so many out of work. They can compel workers to work harder — and complain less — in order to retain their jobs.

And, let’s be clear, the senior executives of these tech companies’ leaders know each other, interact socially and professionally, and collectively have shifted their worldviews — formerly a leftish libertarianism — into something more oligarch-ish over the past decade.

They may not even be communicating directly. Instead, they telegraph their plans by interviews with the press, public announcements, speaking at corporate or shareholder events, and company town halls. They are showing their hands, openly, and others are liberated to follow with similar draconian policies.

Leave aside the evidence from researchers like Nick Bloom and others that remote work — done sensibly — leads to at least equivalent levels of performance by businesses adopting it — and at considerable benefit to the average worker.

But the point isn’t performance: it’s power.

This issue brings to mind Hannah Arendt's concept of the First Right: the right to have rights. Her insight was that rights come from citizenship, and those without have no rights. She first wrote of this in 1949, and in her work, Origins of Totalitarianism, in 1953.

U.S. workers are, in the context of their relation to the businesses that employ them, only guaranteed the few rights that their governments — federal, state, and local — afford them, and those are astonishingly few here in the U.S. But it is only the governments that see them as citizens.

In terms of the ‘private governments’ within business — to use Elizabeth Anderson’s term — workers are really on a par with the stateless people that Arendt considered when thinking of the ‘right to have rights’. Your employer does not consider you a ‘citizen’ of the private government that it is: from their point of view, you are a stateless nobody, an annoyance, an expense on the balance sheet to be culled at the first opportunity.

Do businesses agree that workers have a right to have rights? Other than those enforced by the state, the ordinary employees of the tech sector have been made the target of an intentional or coincidental power play, and moved from one side of the playing board to the other, like a Monopoly top hat or shoe.1

And it’s not just the tech sector that has no ‘first right’, it’s the entire stratum of people who work for a living. And, as such, nearly all people who work for a living are subject to a form of ‘slow violence’, the unremitting awareness of their precarity, and lack of Arendt’s ‘first right’ and all the other rights that follow from it.2

And this inconvenient fact won’t be changed by those calling the shots. We’d need something like a revolution to change this system, and I don’t think it’s hiding just around the corner. Not likely in the world of 2025, just a few weeks away.

So my first prediction for 2025: expect no revolution in the next year, if we can extrapolate from recent trends. It may require years of ‘slow resistance’.3

Factoids

That’s a lot of heads rolling.

The tech industry laid off more than 264,000 employees last year, 100,000 more than the year before, according to Layoffs.fyi, which serves as a reminder that tech workers may have lost their greatest perk of all: job security.

| Nico Grant, who you can blame for inspiring my screed, above.

…

Fashion needs refashioning.

The fashion industry […] is part of a global sustainability problem,” said [Robert] Gentz [co-chief of Zalando, Europe’s largest online fashion retailer], pointing to the fact that 40 percent of all apparel in western wardrobes is never worn.

That’s a surprisingly high.

…

In 2017, a Medium article analyzed 32 rom-coms from the 1990s and 2000s and discovered that while all starred smart, ambitious women, only four featured a woman with a higher-status job than her male love interest.

I am not surprised.

…

The future of food has to be industrial.

[Agriculture] has already overrun about two of every five acres of land on the planet, and farmers are on track to clear an additional dozen Californias worth of forest by 2050.

| Michael Grunwald, who thinks we need to become way more efficient at growing food, because we have to stop taking over grasslands and forests to produce enough for an ever-demanding world.

Elsewhere

What makes a Leader?

Neil Greenfieldboyce cited in 2020 then-new research on the deep psychology of leaders. That research [emphasis mine],

suggests that people who end up in leadership roles of various sorts all share one key trait: Leaders make decisions for a group in the same way that they make decisions for themselves. They don't change their decision-making behavior, even when other people's welfare is at stake.

That may come as a bit of surprise, given that most lists of key leadership qualities focus on things like charisma and communication skills.

"Previous research has mostly focused on these kinds of either personality characteristics of a leader, or situations where individuals are likely to lead," says Micah Edelson, a neuroscientist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. "But we don't know much about the cognitive or neurobiological process that is happening when you are choosing to lead or follow — when you're faced with this choice to lead or follow."

He notes that the decisions of leaders can affect the lives of many others. "It's not always that easy to make such a choice, and it's something that could be even a little bit aversive to you, to make a choice that impacts other people," says Edelson. "And there are some people that seem to be able to do it; some people don't. So we were interested in looking at that."

Note that this leadership trait doesn’t translate consistently into something that could objectively be considered ‘good’ leadership:

But Sharot says the researchers have identified something about leadership that can hold true regardless of a leader's style.

"You can have authoritarian leaders who like to have the ultimate control," she says. "You can have democratic leaders who want to lead according to the will of the people. You have leaders who are risk-takers, leaders who are risk-adverse and conservative and so on."

But what's really interesting about this work, she says, is that these different types of leaders' decision-making behavior stays the same regardless of whether the outcome affects only themselves or other people. "What this paper shows is that all these types of individuals, all these types of leaders, have something in common."

Witness the decision-making of the tech companies layoffs and RTO demands, which are — at least from my viewpoint — objectively bad for the many people’s heads they fall upon. However, whether saint or sinner, those leaders do share this common characteristic.

…

Strategy vs Execution

In "Strategy vs Execution" is not a helpful distinction, Tim Casasola reaches back into industrial history and wants to set this straight:

This separation of strategy and execution [that he witnessed in working with startups] is more harmful than helpful. It’s a distinction that’s woefully outdated.

Let’s go back to a time that pre-dates the internet: 1910, during the Second Industrial Revolution. This was a time when manufacturing began to scale standard practices, leading to mass production and a new wave of globalization.

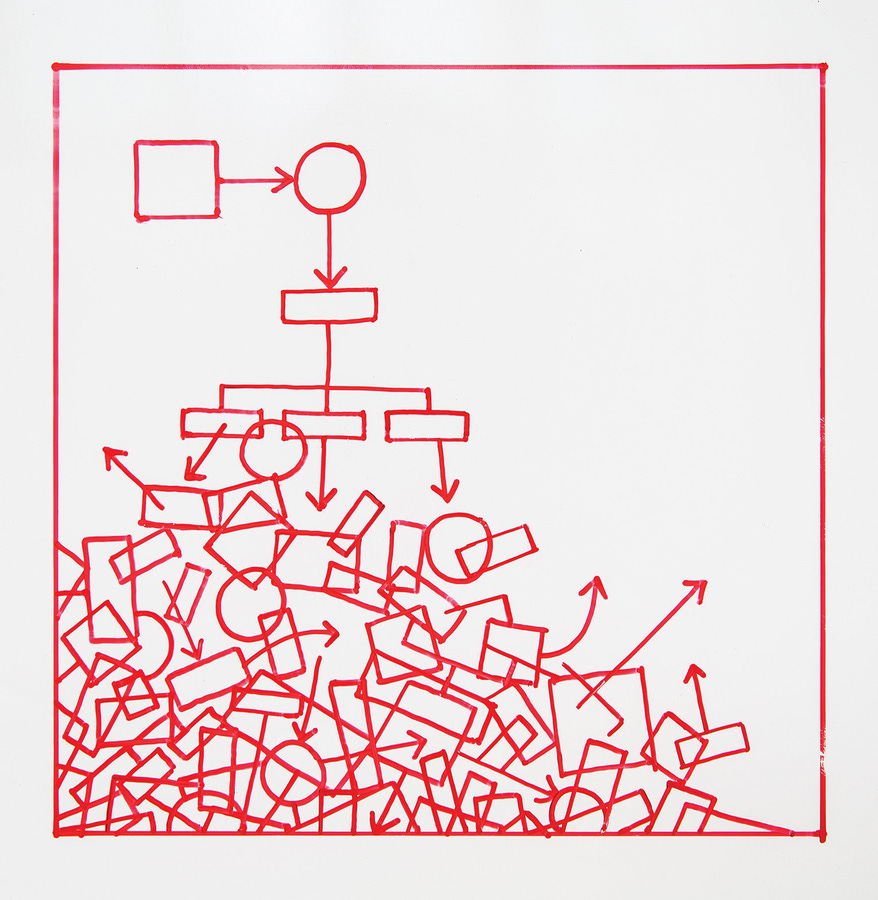

Frederick Taylor, a mechanical engineer who sought to improve industrial efficiency, coined a theory called scientific management. Scientific management was all about optimizing economic efficiency and labor productivity. It was super influential at the time. And some of its themes still live on today (for better and for worse).

I want to home in on one specific principle published in The Principles of Scientific Management:

Allocate the work between managers and workers so that the managers spend their time planning and training, allowing the workers to perform their tasks efficiently.

Taylor advocated for two kinds of employees: managers and workers. And he believed it was most efficient for managers to plan and workers to do.

This idea was in a book published in 1911. Yet we still carry these assumptions at work today: almost every company separates strategy and execution and has managers and doers.

I like how the Helsinki Design Lab challenges this separation between thinker and doer. From page 40 of Recipes for Systemic Change:

Without the broader stewardship arc, the design process is easily all about thinking and not doing — this is precisely what we see to be the difficulty with the ‘design thinking’ debate and its over-emphasis on helping people think differently. In the context of strategic design, ideas are important, but only when they lead to impact. Part of this is appreciating the quality with which an idea is executed and recognizing that quality of execution and quality of strategy are equally important.

I suggest you read the whole thing, but the gist is this:

Ideas are important only when they lead to impact. And execution and strategy are equally important.

[…]

Everyone is a thinker and doer.

Of course, managers are thinking more than individual contributors. And individual contributors are doing more than managers. But if you’re an individual contributor, it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be curious about how your work advances your company’s strategy. And if you’re a manager, it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be willing to do actual work.

Get rid of the idea that strategy and execution are separate things. Instead, put your beliefs to the test by acting upon them and seeing what you learn.

The the entire superstructure of modern business — which still leans heavily into the scientific management mantra — is questionable, along which the bronze age thinking about a managerial class that thinks and a rank-and-file that does what it is told.

In writing this issue, I learned that the Monopoly shoe is no more. It has been replaced by a cat, or a T-rex, I think.

from Slow Resistance: Resisting the Slow Violence of Asylum | Natasha Saunders, Tamara Al-Om. ‘Slow Resistance as an umbrella concept through which to understand the resistance of individuals subjected not just to a particular form of power, but to a particular form of violence – Slow Violence.’

Ibid.