Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.

| Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

Four-Day Work Week, Once Again

I read Inside the Four-Day Workweek Experiment, by Isabella Kwai, and Tom Jamieson, which relates the progress on a second effort by the British advocacy group 4 Day Week to promote a shorter workweek in the UK.

The effort, which appears to be successful, is a follow up to a 2022 push:

After a previous pilot in 2022, 56 of 61 participating companies, or 92 percent, said they would continue with the four-day week, the group said. It is hoping to pave the way for a 32-hour, four-day week to be enshrined under British legislation, reducing the maximum number of hours currently allowed by law. Similar efforts have taken hold in Iceland, New Zealand, Scotland and the United States.

[…]

After the first trial, from June to December in 2022, 70 percent of the nearly 3,000 employees involved said they felt a decrease in stress and burnout, while companies reported no negative impact to their revenue, according to a report by the program’s organizers.

The motivation appears to be a combination of worker well-being (based on short hours) and increased productivity:

“It’s sound business sense,” said Geoff Slaughter, a co-founder of BrandPipe. “If you’ve got a team that’s happy, you’re less likely to lose them.”

“Having looked at the research, frankly it seemed like a no-brainer,” said Anne-Marie Irwin, a partner at Rook Irwin Sweeney, a British law firm specializing in public law and human rights that is also participating in the trial.

Yes, the companies had to work at coordinating non-overlapping days off, since the companies couldn’t simply not close one day of the week — since they have to operate in a world of five-day work weeks.

Most of the article is dedicated to describing how the companies have shifted operations to support greater need for coordination and communications.

After the current trial, the campaign is planning to present the results to British officials, who have signaled an interest in reforming labor laws for British workers.

“We want to see the four-day week become the normal way of working in this country by the end of this decade,” said Joe Ryle, director of the 4 Day Week Campaign.

The bottom line?

“The data supports our impression, which is that we’re all working more efficiently,” said Alex Rook, a [Rook Irwin Sweeney] partner. Still, he said, it had taken effort: “Change is difficult.”

They were waiting before committing to the arrangement, but there was plenty of positivity so far. “At the moment, everybody is really enjoying it, really happy to be doing it,” Mr. Rook said. “The numbers look good.”

…

Okay, great. But this is 2025, right? A successful trial in 2022 did not lead to a groundswell of enthusiasm for transitioning nationwide to a four-day workweek, but I suppose we have to made allowances for companies grappling with the after effects of the pandemic and financial inflationary crisis that followed.

Here’s a post I wrote in 2015 about the same promising idea, and making the same case about improved well-being AND increased efficiency, Will the flex week evolve into the four-day work week?:

Allowing flexibility in work schedules — like working from home on Fridays — is a simple way to motivate and engage workers. But some innovative companies have started to advocate a four day work week, both as a way to allow workers to spend more time with families and outside activities, but also as a way to focus attention on what’s essential while at work.

Jason Fried, the CEO of Basecamp (formerly 37signals), wrote in the NY Times in 2012 about the four day work week:

There’s one surprising effect of the changed schedule: better work gets done in four days than in five. When there’s less time to work, you waste less time. When you have a compressed workweek, you tend to focus on what’s important. Constraining time encourages quality time.

Fried’s comments are from 2012, and I pulled together other advocates arguing for a four-day week in 2015. Over a decade later, companies are still slavishly holding to a five-day workweek.

In 2019, I once again wrote about the imminent blossoming of the four-day workweek:

Cassie Werber talked with Andrew Barnes of Perpetual Guardian, a financial services firm in New Zealand about his experience in trialing and then transitioning permanently to a four-day workweek for the 240-person company.

The bottom line, again:

'78% of staff felt able to manage work and other commitments after the trial, compared to 54% before'. And with that, 'productivity increased by about 20% during the trial, while revenue remained steady'.

And the biggest barrier?

Barnes says the people who were most resistant were middle management. They’ve also been the people most deeply changed.

“If you’ve got a leadership team, the challenge that leaders have is that they then say: “I’ve been conditioned all my life that working longer equals working harder. And I am responsible for output,” Barnes says. “And so the people that are most skeptical about this are actually middle management, because they’re the people who are going to have to deliver on the policy.” Perpetual Guardian’s four-day week trial ended up exposing weak points in leadership, and improved staff engagement to the extent that middle managers found they could delegate more easily, Barnes says. “It actually opened their eyes to being a leader rather than a manager.”

But, here we are, and I bet middle management and outmoded thinking about ‘more hours = more productivity’ is still the major modality inside workplaces, instead of the key insight that people are more productive — less stressed and happier — when they work a day less a week.

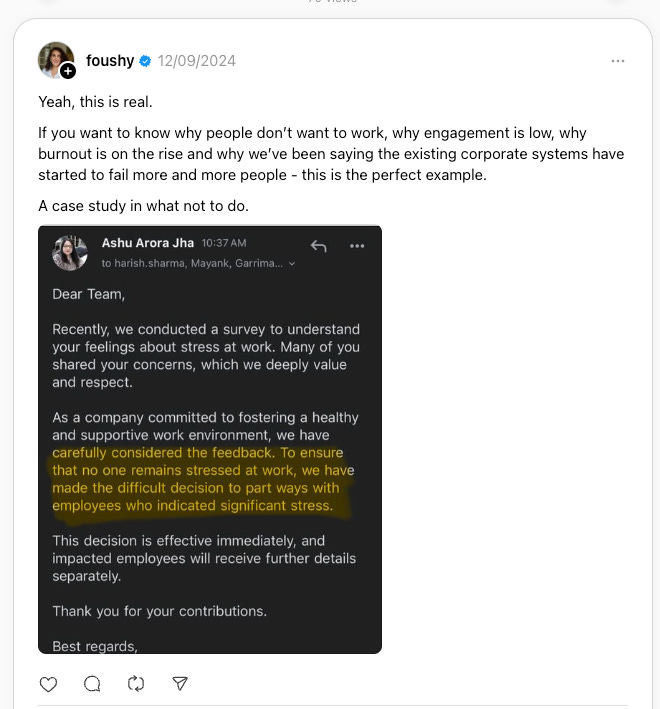

And the newest proof that this negative and ignorant mindset is still the norm? From Rahaf Harfoush:

Yes, this executive fired all the employees of her company, YesMadam, that responded to a survey about stress at work. (She has since walked back the brouhaha, claiming it was a PR stunt to raise awareness about stress, but what actually went on is unclear.)

Still, the current push by tech giants to get employees back in the office five days a week — or face termination — flies in the face of mounting evidence that less time at work leads to higher productivity, when managed well.

Factoids

Meritocracy is not only false, it’s bad for you.

Clifton Mark shares his research into our cultural delusions about merit:

Most people don’t just think the world should be run meritocratically, they think it is meritocratic. In the UK, 84 per cent of respondents to the 2009 British Social Attitudes survey stated that hard work is either ‘essential’ or ‘very important’ when it comes to getting ahead, and in 2016 the Brookings Institute found that 69 per cent of Americans believe that people are rewarded for intelligence and skill. Respondents in both countries believe that external factors, such as luck and coming from a wealthy family, are much less important. While these ideas are most pronounced in these two countries, they are popular across the globe.

[…]

In addition to being false, a growing body of research in psychology and neuroscience suggests that believing in meritocracy makes people more selfish, less self-critical and even more prone to acting in discriminatory ways. Meritocracy is not only wrong; it’s bad.

Research shows embracing the role of luck in societal advantage increases generosity. Companies that extol meritocracy as a core value ‘assigned greater rewards to male employees over female employees with identical performance evaluations’.

…

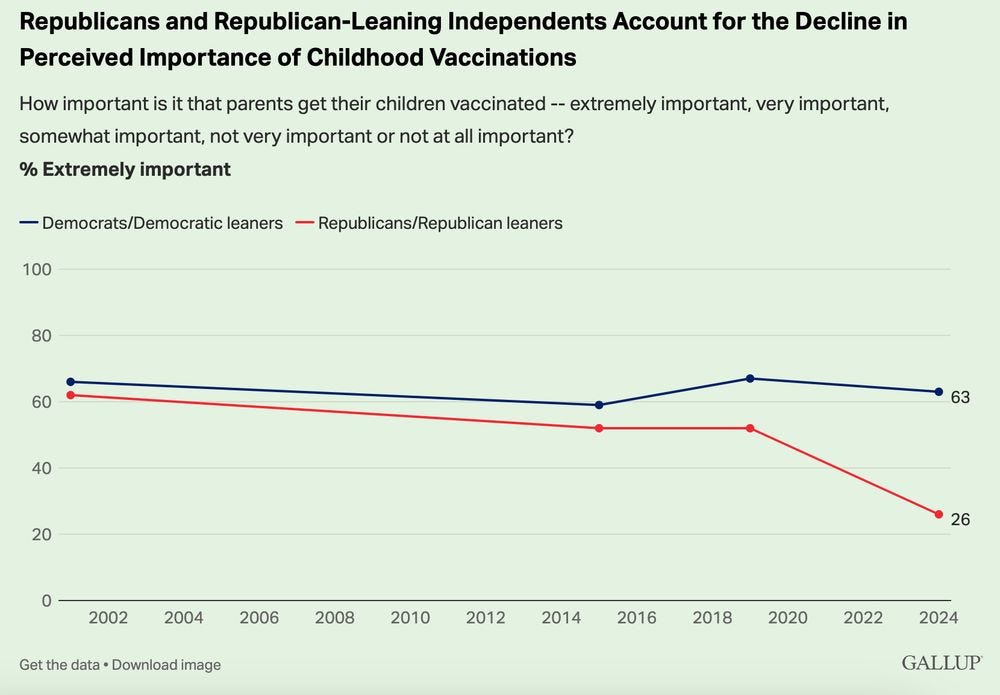

Republicans are defecting from modern public health.

The share of Republican adults who say it's "extremely important to get their children vaccinated" has declined by more than 50 percent in five years.

And that is dangerous for all of us, not just their endangered children.

…

Business leaders out of touch with the ‘disaffected’.

This year, PricewaterhouseCoopers surveyed business executives and found 90 percent of them thought customers trusted them a lot, while only 30 percent of customers surveyed agreed.

| Kristen Soltis Anderson, who goes on to explain:

In my work discussing public opinion surveys with executives, I am always struck by the number of successful leaders who are surprised that more Americans do not give them or their industry the benefit of the doubt or see the good in what they are doing.

[…]

Not long ago many Republican Party leaders and plenty of G.O.P. voters believed in the value of business, the need to protect business from government interference and the virtues of “job creators.” In 2012, for instance, only 23 percent of Republicans said they had “very little” or no trust in “big business,” while 38 percent had “quite a lot” or “a great deal” of trust. By 2023, those numbers had flipped, with high trust in big business falling by 20 points.

The American population is becoming increasingly disaffected — increasingly distrustful of institutions and those that are supposed to lead them for the common good — and business is just such an institution.

Elsewhere

The Berlin Conference Declaration

Looking back over the year’s research (preparing for a retrospective issue of workfutures.io), I returned to what I thought was going to be a turning point in economics-driven public policy: The Berlin Summit Declaration. As Dani Rodrik, Laura Tyson, and Thomas Fricke wrote about a manifesto signed by dozens of leading economists at the ‘Winning Back the People’ conference held in May 2024:

Dozens of leading economists and practitioners convened in Berlin at the end of May for a summit organized by the Forum for a New Economy. Remarkably, the summit led to something resembling a new understanding that may replace the decades-long reign of neoliberal orthodoxy.

But aside from a few articles mentioning the Declaration, I have seen basically no impact on public policy discussions. Another case of ignorance winning?

…

Capturing our daydreams for profit.

In Time After Capitalism, Miya Tokomitsu approaches the work week from a completely different angle: the struggle between workers and work (or bosses) for control of their time, and what might happen if we had more of it to daydream.

British physicist Peter Higgs, nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1980 for discovering how subatomic particles acquire mass, credits his breakthrough to “peace and quiet” and conjectures that the modern academy’s grueling publication requirements would have made it impossible for him to make his discovery, or indeed for his younger self to have an academic career at all.

But we should protect idleness from those who would try to capture our daydreams for profit. Most of our caprices will not be as useful or broadly enlightening as Higgs’s, but that does not make them any less valuable to ourselves. Most of us don’t know what it would feel like to waste time without the nagging feeling that we should be doing something else. What if we were free to find out?

[…]

We could seize this empty, slow time and claim it for ourselves, developing ways of relating to each other that aren’t centered on commodity consumption.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work Futures to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.