Also As An End

Immanuel Kant | The Limits of Digital: Ideas, Creativity, and Cultural Reformation | Factoids | Elsewhen

Act so as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, at all times also as an end, and not only as a means.

| Immanuel Kant, Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

Should be the first principle of politics, and of business. But, alas, too few of those that ply those trades have adopted Kant’s metaphysics.

The Limits of Digital: Ideas, Creativity, and Cultural Reformation

The Decline In Productivity: A Cause or a Clue?

[originally published on Medium, republished here.]

Irving Wladawsky-Berger turns his attention in a recent Wall Street Journal article to the well-known productivity paradox. As Wladawsky-Berger summarizes,

Despite the relentless advances of digital technologies, productivity growth has been declining over the past decade. Investment and interest rates have remained low, and income has continued to stagnate for the majority of workers in the US and other developed economies. The world seems to be stuck in a period of slow growth and no one is quite sure what's causing this apparent contradiction.

Wladawsky-Berger notes that leading economists have suggested various reasons for this paradoxical lack of productivity. Larry Summers has offered up secular stagnation, where companies fall short in investing (consider the cash reserves of Apple and Google, who can't seem to find good returns for investment). Meanwhile consumers buy less than they might, both of which slow growth. Robert Gordon has argued that a global decline in innovation and productivity over the past few decades is a return to an intrinsically lower rate, as was the norm prior to 1900. Other have noted that the world's population growth has slowed in recent decades, and that could act as a brake on productivity. I've written recently (in The Hidden Economics of Ideas) about research by economist Nicholas Bloom and his colleagues that seems to indicate that the costs of finding new ideas are rising:

Across a broad range of case studies at various levels of (dis)aggregation, we find that ideas --- and in particular the exponential growth they imply --- are getting harder and harder to find.

The primary cause of the rising costs of new ideas is that in industries where we have seen steady innovation -- such as in semiconductors -- the number of researchers required to maintain that innovation has been growing steadily. As I wrote,

The researchers believe they have answered the question: can a constant level of research effort generate constant exponential growth in the entire economy or in specific economic niches? The answer seems to be 'no'. Turned around, constant exponential growth requires a growing number of researchers.

It appears, according to Bloom et al, that we need to double the number of researchers every 13 years just to keep the economy growing at the current rate.

There may be additional negative factors contributing to the lack of productivity, or, turning it around, there may be positive factors that could increase productivity if we could only harness them. Some technology observers -- like Erik Brynjolfsson, Daniel Rock, and Chad Syverson in AI and the Modern Productivity Paradox -- have suggested that there is just such a bottleneck in the adoption of the transformative technologies that make up the fourth industrial revolution: the internet, AI, ubiquitous mobility, big data, IoT.

In recent research, Brynjolfsson has returned to this question, this time joined by Seth Benzell, and created a sweeping macroeconomic model to dig into that economic bottleneck. In their Digital Abundance and Scarce Genius, the pair of researchers model the question: what possible factors can be leading to this decrease in productivity, even as digital technologies exist that can scale non-linearly and should therefore be ushering in an expansion of digital capital?

Their answer is the scarcity of an X factor --- or, specifically, a G factor, where G represents the scarcity of genius.

Putting the G in Genius

Benzell and Brynjolfsson start with our current technological situation, pointing out that 'computer processing power has increased by a million-fold in just three decades, while digital storage and digital communications have grown at equally dizzying rates'. They cite the rise of automation and AI as game changers across many industries:

One striking feature of these new technologies is their replicability at low or even zero cost. Any digitizable innovation can spread almost instantly worldwide. Cloud services create a digital fire-hose that gives rapidly expanding companies access to eyeballs, venture finance, connections, effective labor, computation and software.

But if so, why haven't the economic signs of an expected productivity boost appeared? Asking the question in terms of economics, why is wage growth so flat, why are interest rates so low, and investment rates so flat? If there is a killing to be made, why are so many companies sitting on billions in accumulated capital instead of investing in the engines of future productivity? And their answer is that we are bottlenecked, and so all of these anticipated effects are blocked. They state their formulation of the productivity paradox of our time succinctly:

The inputs in our model are traditional capital and labor and a relatively inelastic complement we dub 'genius' or G. When G is relatively abundant, the economy approximates a two-factor one [that is, an economy based on only traditional capital and labor]. But as G becomes relatively scarce, it becomes a bottleneck for output and captures an increasing share of national income. We show that when traditional inputs are sufficiently complementary to G, innovations in automation technology can reduce both labor's share of income and the interest rate.

As the term 'genius' implies, the authors lean toward the interpretation that the G factor is the relative scarcity of human superstars, those who can come up with new ideas, new syntheses of the novel and the established — those that can go where today's AI cannot yet reach on its own. The outcomes of the activities of these superstars are assets that the company may exploit or sell, independently of the superstars, a transferable — or alienable — asset:

For concreteness, our primary interpretation for G is superstar individuals. They may be exceptionally gifted with the ability to come up with an exciting new idea, sort through bad ideas for a diamond in the rough, or effectively manage a business. If these good ideas are owned by and accumulate within firms, they correspond to a kind of alienable genius.

This thinking lines up with other research, such as Sam Walker's arguments in The Economy's Last Best Hope: Superstar Middle Managers, in which he lays out the result of a major Gallup study [emphasis mine]:

Five years ago, the Gallup organization embarked on one of the most ambitious deep dives it has ever conducted; an analysis of the future of work based on a decade of input from nearly 2 million employees and more than 300,000 business units. The results confirmed something Gallup had seen before: a company's productivity depends, to a high degree, on the quality of its managers.

What no one saw coming, however, was the sheer size of that correlation---something Gallup calls "the single most profound, distinct and clarifying finding" in its 80-year history. The study showed that managers didn't just influence the results their teams achieved, they explained a full 70% of the variance. In other words, if it's a superior team you're after, hiring the right manager is nearly three-fourths of the battle.

There is still enormous wiggle room in these formulations about G from Gallup, and Benzell and Brynjolfsson. If it boils down to human genius that still begs the question of what sort of genius and how is it articulated with the non-geniuses in the organizations involved? Are these people creating intellectual property? Are they more knowledgeable in exploiting value from 'virtual real estate', the creation of internet-based platforms and their ecosystems?

The limit case of intangible assets, where the adjustment cost is infinite or nearly so, can be thought of as 'virtual real estate'. Intellectual property, including monopolies created by patents, copyrights, or trade secrets, is one category of virtual real estate. It can also reflect an exclusive opportunity to profit from strong network effects (including two-sided networks and platforms), control of an indispensable standard, or privileged access to exceptional supply-side economies of scale. All three are common in digital goods, which typically have high fixed costs and low or zero marginal costs. The owners of the social network that consumers have coordinated on may therefore be thought of as collecting rents on virtual real estate. This is still true if there were, ex-ante, many distinct and equally good networks for a particular application. Only one can become the ex-post focal network after some combination of ingenuity, effort, and random events makes it pre-eminent.

This suggests G could be the advantage conferred from virtual real estate, or the knowledge of how to develop that real estate. At the same time, are these companies the best at getting the organizational culture to shift away from older, traditional ways of doing business and embracing new ways of work that harness the new economics of a post-industrial future? And making the costly investments so that digitization of business operations is possible:

Alternatively G can be interpreted as a marginally costly intangible asset. If making full use of AI requires firms to make large, time-consuming, hard-to-accelerate investments in digitizing their business processes, then firms that have already bypassed this bottleneck will make large operating profits. From this perspective, the genius may lie in the system itself, not in any single individual.

Benzell and Brynjolfsson cede the possibility that G is not actual human superstars, per se. They explicitly reference the research of Bloom and his colleagues, granting that a dearth of ideas may be all or part of G. However, the authors remain impartial as to whether the G factor is superstars, ideas, intellectual property, a larger investment in the transition to a digital organization, or accession to ownership of virtual real estate (such as a niche-dominant platform ecosystem).

We suggest several microfoundations of this aggregate relationship and explore implications. Our 'microfoundations' are not mutually exclusive and may ultimately be revealed as a simplified representation of a complex underlying trend.

The Implications of G

Benzell and Brynjolfsson explicitly address the implications of G as a potentially diminishing constraint. They cite Le Chatelier's Principle from chemistry: if a constraint (such as a change in pressure, temperature, or concentration of a reactant) is applied to a system in equilibrium, the equilibrium will shift so as to tend to counteract the effect of the constraint. In our domain of discussion the constraint is G. Companies --- and society as a whole --- have strong incentives to counteract a scarcity of G.

Therefore, you'd expect massive efforts to increase the production of new ideas, to hire superstar managers, to transition to a new digital foundation in business operations, and to take the high ground in the battle for platform-based virtual real estate. We know that all of these things are happening, but not in sufficient numbers to unstick productivity across the board.

The final implications are likely to lie in the 'near adjacent' (nearby domains that are interacting with the area of our focus) and not just the intensification of what has come before. After all, what we have done so far has led us to the current productivity impasse. And in the near adjacent lie truly novel solutions for more G, such as more advanced AI, intended to produce more new ideas (or more rapidly reject bad ones).

To me, smarter AI sounds like the extension of the current narrative, and less of a breakthrough than a second answer for G. Instead, I look to the broad dissemination of the protocols, practices, and technologies that underlie platform ecosystems, and a transition of global businesses into massively-connected assemblages of interdependent organizations united by ecosystem economics. This could be the new stage of 'replicability at low or even zero cost' expansion of these economics, but one that relies on the adoption of new ways of work by people, teams, and organizations, rather than the singularity of some next stage in AI intellect.

I'd rather bet on organizations made of people, even if we do get AI working on sifting through the idea pile for us.

Factoids

Going up?

China build a lot of apartment building between 1980 and 2000 to house rural igrants. Now, with an aging population, the country is retrofitting those buildings with elevators. To finance that, elevator companies are fronting the construction and plan to make back the money (with interest) over the following 15 years by changing per ride fees for resident using facial recognition.

Hat tip to Adam Tooze.

…

How many three-pointers?

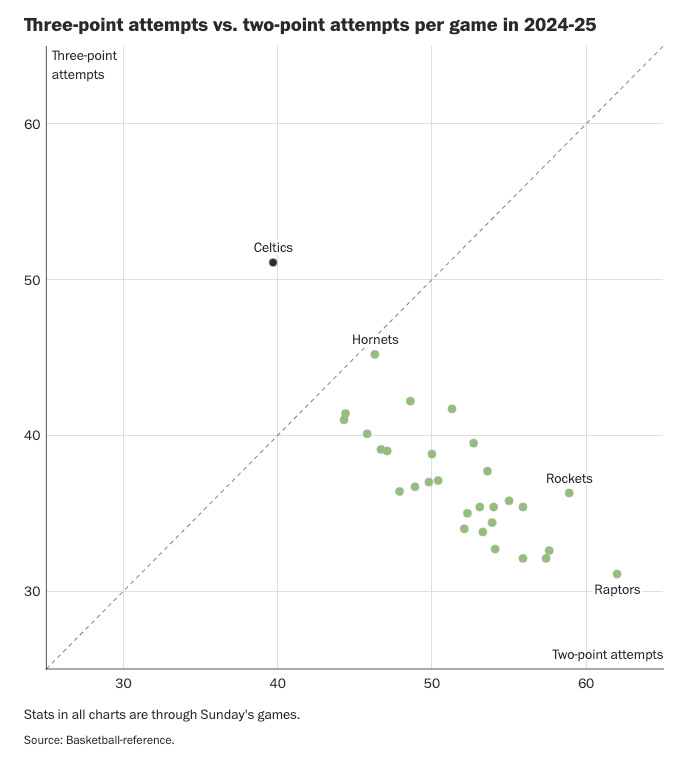

Entering Tuesday night’s game against the undefeated Cleveland Cavaliers, Boston is the only team this season — and just the third in league history — to attempt more three-pointers than two-pointers. While Harden’s Houston Rockets leaned more on threes than twos in 2018-19 and 2019-20, the Celtics have distorted the outside-inside balance more than any team in history by taking 51.1 three-pointers and 39.7 two-pointers per game.

…

Crisis relativity.

Even a deadly disease is only a crisis when we treat it like one. If that’s difficult to believe, keep in mind that heart disease has killed nearly 100 million people in the time it took Covid to claim seven million or so.

…

Many old landfills are being mined for copper, because demand is so high.

Glencore estimates that global copper supply must grow by about one million metric tons a year through 2050. That would require annually adding the equivalent of the world’s largest mine, Chile’s Escondida.

Reading about mining landfills reminds me of Bruce Sterling’s line:

The frontiers of the future will be the ruins of the unsustainable.

Elsewhen

I was writing a great deal in this vein in the early `00s, and it is one of the reasons that I was doing a lot of public speaking, and, as well, why I was growing despondent about these sort of pleas falling on… well, if not deaf then at least relatively unresponsive ears.

Oh, and there’s a holiday message buried in there.

Working Toward Life Balance | Stowe Boyd (2010)

An interesting twist on the work/life balance meme caught my eye:

Mitch Joel, The Myth Of Work Life Balance

There is no such thing as work/life balance. By even saying there is such balance, you’re making an internal agreement that work is not a part of a healthy life, and I just don’t buy it. Like you, I put a good chunk of my waking hours against the work I do. I can’t accept that it doesn’t constitute an important and real part of my life. In the end, I’m not looking for work/life balance… I’m looking for life balance.

I have said for years that I’ve given up on finding a balance in life, I’m going for depth instead. But it’s not really the case. It’s just that I am looking for something larger.

I agree with the spirit of Joel’s post, in which he deftly turns the work/life balance on its ear. But his rejoinder is all wrong for me.

He’s right when he says we need balance in our lives, including whatever it is we are doing as ‘work’. But his three categories — personal, business, and community — simply create a slightly more complex balancing act, and don’t go far enough. It’s too small.

Instead, consider the contour of a well-ordered humanism laid out by Claude Levi-Strauss:

A well-ordered humanism does not begin with itself, but puts things back in their place. It puts the world before life, life before man, and the respect of others before love of self.

So, for me, balance can’t be self-centered, it must be world-centered.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work Futures to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.