A Paradox of Leadership

Sam Walker, Ursula Le Guin | Boreout | Factoids | Elsewhere, Elsewhen

One of the paradoxes of leadership is that the better you are at it, the less people tend to notice you. When leaders remain calm and consistent, and unite people over a sensible course of action, observers may be less likely to recognize their influence or give them proper credit.

| Sam Walker, What Football Can Teach Politics

When I read that line, it reminded me of the 17th chapter of the Tao Te Ching.

Here’s Ursula Le Guin's translation:

True leaders

are hardly known to their followers.

Next after them are the leaders

the people know and admire;

after them, those they fear;

after them, those they despise.To give no trust

is to get no trust.When the work's done right,

with no fuss or boasting,

ordinary people say,

Oh, we did it.

Boreout

We are beset by an almost romantic affliction: boreout, burnout’s left-handed twin.

Bryan Lufkin does a good job plainly laying it out:

While burnout is linked to long hours, poor work-life balance and our glamourisation of overwork, boreout happens when we are bored by our work to the point that we feel it is totally meaningless. Our job seems pointless, our tasks devoid of value.

Lufkin quotes Lotta Harju, a researcher in organizational behavior:

Harju describes boreout as “kind of a signature syndrome” of the pandemic; our ennui fueled by too much time in Zoom meetings, surrounded by the same four walls. “My hope is that these boreout-related trends will force some organisations to re-think their human resource philosophies and policies, and organise work in a more sustainable way in general in the post-pandemic era.”

It would be my hope too, but too little is being done internally in businesses to counter boreout, and perhaps it's inevitable in a world like ours -- dominated by streaming apps, smartphones, and the immediacy and enormity of the polycrisis we are living in -- that our capacity to approach our work (and non-work) as opportunities to find meaning has declined.

I’ve collated some other writing on boreout.

In Why Boredom At Work Is More Dangerous Than Burnout, Lindsay Kohler offers practical advice about countering the behaviors and mindsets that lead to boreout, and cites a number of recent studies that explore different aspects of this 'new' workplace ill:

"Boreout" at work is chronic boredom, and studies have shown it can cause depression, anxiety, stress, insomnia and higher turnover. Boredom is an emotional state characterized by feeling unstimulated, unfocused and restless, yet lacking the desire to engage. Or in short — boredom exists when we are mentally idle. While individual differences in how prone we are to boredom exist, everyone has felt it at one point or another at work. This boredom matters because a Korn Ferry survey claims that boredom is the top reason why people leave their jobs.

Boredom is brought on by a combination of factors. It can be a lack of stimulation, i.e. we find our work uninteresting and unengaging. Or perhaps people don't have enough work to do — too much leisure time can also bring on boredom. It's also compounded by a mismatch between expectations and reality. The New Yorker writes that "modern capitalism multiplied amusements and consumables, while undermining spiritual sources of meaning that had once been conferred more or less automatically. Expectations grew that life would be, at least some of the time, amusing, and people, including oneself, interesting—and so did the disappointment when they weren't." One can also argue that modern life has also brought on entire industries where people secretly believe that the job they work doesn't need to be done.

The citation to the New Yorker led me to Margaret Talbot’s magisterial treatment of boredom (and boreout): a grand tour of philosophical, literary, and scientific explorations of boredom and its offspring, boreout. A must read. One fragment:

Boredom, it’s become clear, has a history, a set of social determinants, and, in particular, a pungent association with modernity. Leisure was one precondition: enough people had to be free of the demands of subsistence to have time on their hands that required filling. Modern capitalism multiplied amusements and consumables, while undermining spiritual sources of meaning that had once been conferred more or less automatically. Expectations grew that life would be, at least some of the time, amusing, and people, including oneself, interesting—and so did the disappointment when they weren’t. In the industrial city, work and leisure were cleaved in a way that they had not been in traditional communities, and work itself was often more monotonous and regimented. Moreover, as the political scientist Erik Ringmar points out in his contribution to the “Boredom Studies Reader,” boredom often comes about when we are constrained to pay attention, and in modern, urban society there was simply so much more that human beings were expected to pay attention to—factory whistles, school bells, traffic signals, office rules, bureaucratic procedures, chalk-and-talk lectures. (Zoom meetings.)

Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard considered boredom a particular scourge of modern life. The nineteenth-century novel arose in part as an antidote to the experience of tedium, and tedium often propelled its plots. What was Emma Bovary, who arrived in 1856, if not bored—by her plodding husband, by provincial existence, by life itself when it failed to show the glittering colors of fiction? Oblomov (the eponymous novel by Ivan Goncharov appeared three years after Gustave Flaubert’s) is a superfluous man on a superannuated feudal estate who passes the time with his family in thick silence and bouts of helplessly contagious yawning. Though it was possible in the English language to be “a bore” in the eighteenth century, one of the first documented instances of the noun boredom’s being invoked to describe a subjective feeling did not appear until 1852, in Dickens’s “Bleak House,” afflicting the aptly named Lady Dedlock.

Heidegger, one of the preeminent theorists of boredom, classified it into three kinds: the mundane boredom of, say, waiting for a train; a profound malaise he associated not with modernity or any specific experience but with the human condition itself; and an ineffable deficit of some unnameable something that sounds thoroughly familiar to us. (This third kind might have made a good additional verse for Peggy Lee in her languid “Is That All There Is?”) We are invited to a dinner party. “There we find the usual food and the usual table conversation,” Heidegger writes. “Everything is not only tasty, but very tasteful as well.” There was nothing unsatisfactory about the occasion at all, and yet, once home, the realization arrives unbidden: “I was bored after all this evening.”

I also highly recommend Burnout or Boreout? It’s Always About the Lack of Control, in which Anne-Laure Le Cunff channels her experience with burnout and her attention to the context for boreout to set the stage for personal advice for those contending with our newest workplace affliction. She offers this [emphasis mine]:

Psychologist Steve Savels explains: “You become irritated, cynical, and you feel worthless. Although you don’t have enough to do, or what you have to do is not stimulating you enough, you get extremely stressed. (…) With a boreout, you get stuck in your ‘comfort zone’ for too long, until your personal development comes to a halt.”

Burnout is when you are overstimulated, and boreout is when you are understimulated. Both leave you exhausted, feeling empty, and unable to cope with the demands of work and life. So, how can you restore your energy and your enthusiasm?

Weltschmerz

In the final analysis, boreout is a late-stage capitalism disease-of-work. I feel that it is one side of a coin — the work side — while on the other the coin shows its worldly face, and manifests as a deep world-weariness, ennui, a deadening of the sense of curiosity, or, to use a term of the romantic era, weltschmerz:

Nostalgia is the defining emotion of the postmodern era. Now in the postnormal, it's weltschmerz, the 'homesickness for a place you have never seen', a world we may never occupy.

| Stowe Boyd, via twitter

The yearning for a job we may never find, and the consequent sense of meaning that may never be realized.

Factoids

Asshole bosses create more chaos than you think.

The prevalence of asshole bosses1 is confirmed by careful studies. A 2007 Zogby survey of nearly eight thousand American adults found that, of those abused by workplace bullies (37% of respondents), 72% were bullied by superiors. Stories about the damage done by bully bosses are bolstered by systematic research. University of Florida researchers found that employees with abusive bosses were more likely than others to slow down or make errors on purpose (30% vs. 6%), hide from their bosses (27% vs. 4%), not put in maximum effort (33% vs. 9%), and take sick time when they weren’t sick (29% vs. 4%). Abused employees were three times less likely to make suggestions or go out of their way to fix workplace problems. Abusive superiors also drive out employees: over 20 million Americans have left jobs to flee from workplace bullies, most of whom were bosses.

| Robert L. Sutton, Good Boss, Bad Boss

Note that Sutton also pointed out that team performance is always improved by removing a bully, ‘even when the bully was a high performer’.

…

British marshland: a barrier, not a wasteland.

Over the centuries, marshland was increasingly viewed as unproductive. Thousands of acres were drained and turned into arable land or developed for housing and industry. Since 1860, Britain has lost 85 percent of its salt marshes, according to the U.K. Center for Ecology and Hydrology, a research institute.

| Rory Smith, Andrew Testa, A Radical Approach to Flooding in the UK: Give Land Back to the Sea

The authors also note ‘In September, a month’s rain fell in a single day in some parts of England. The 18 months to March 2024 were England’s wettest in recorded history.’

…

Is McDonald’s Quarter Pounder Too Big to Fail? Yes, thanks to an innumerate public.

A recent E.coli outbreak led to old history about the Quarter Pounder coming to light. Hank Sanders reported:

A&W, a competing fast food brand, tried taking on the Quarter Pounder in the 1980s and learned that their one-third-pound patty was less popular because Americans believed a quarter was bigger.

Oy vey.

Elsewhere

Re-skilling won’t lead people to move to more dynamic locations for work.

From Bloomberg:

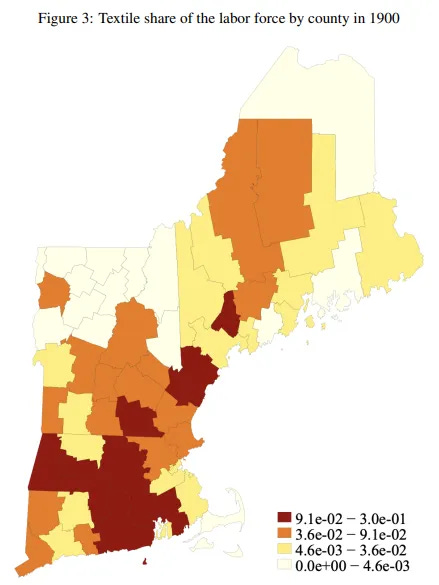

A Boston Fed discussion last week examined the impact of de-industrialization on migration patterns — which showed, perhaps surprisingly, that even in the absence of a social safety net, people tend to stay in place despite the economic deterioration.

The demise of New England’s textile industry in the 1920s offers excellent raw material, because it pre-dates the introduction of things like unemployment insurance. Brandeis University economist Jiwon Choi found that towns walloped by plant closures actually tended to see less out-migration than others.

Some workers shifted to lower-paid jobs in agriculture. Younger ones sought more education, though that didn’t do much to help their eventual employment outcomes — they were “left facing the same negative local economic shock as the others.” Less-wealthy households were less likely to move, suggesting the cost of out-migration was a barrier.

Among the takeaways for policymakers: simply boosting education or training may not prove effective in the absence of new industries for people to turn to and a high cost of moving to a more dynamic location.

Negative evidence for training after layoffs or plant closings. Remember Janesville, Wisconsin and Amy Goldstein’s analysis in Janesville.

Elsewhen

Your Lifestyle Has Already Been Designed — David Cain (2013)

David Cain has started working in Canada again after a seven-month backpacking trip across New Zealand and other faraway lands, and the juxtaposition of the two ways of life leads to some interesting observations about the 40-hour work week:

an excerpt

The eight-hour workday developed during the industrial revolution in Britain in the 19th century, as a respite for factory workers who were being exploited with 14- or 16-hour workdays.

As technologies and methods advanced, workers in all industries became able to produce much more value in a shorter amount of time. You’d think this would lead to shorter workdays.

But the 8-hour workday is too profitable for big business, not because of the amount of work people get done in eight hours (the average office worker gets less than three hours of actual work done in 8 hours) but because it makes for such a purchase-happy public. Keeping free time scarce means people pay a lot more for convenience, gratification, and any other relief they can buy. It keeps them watching television, and its commercials. It keeps them unambitious outside of work.

We’ve been led into a culture that has been engineered to leave us tired, hungry for indulgence, willing to pay a lot for convenience and entertainment, and most importantly, vaguely dissatisfied with our lives so that we continue wanting things we don’t have. We buy so much because it always seems like something is still missing.

Western economies, particularly that of the United States, have been built in a very calculated manner on gratification, addiction, and unnecessary spending. We spend to cheer ourselves up, to reward ourselves, to celebrate, to fix problems, to elevate our status, and to alleviate boredom.

Can you imagine what would happen if all of America stopped buying so much unnecessary fluff that doesn’t add a lot of lasting value to our lives?

The economy would collapse and never recover.

All of America’s well-publicized problems, including obesity, depression, pollution and corruption are what it costs to create and sustain a trillion-dollar economy. For the economy to be “healthy”, America has to remain unhealthy. Healthy, happy people don’t feel like they need much they don’t already have, and that means they don’t buy a lot of junk, don’t need to be entertained as much, and they don’t end up watching a lot of commercials.

The culture of the eight-hour workday is big business’ most powerful tool for keeping people in this same dissatisfied state where the answer to every problem is to buy something.

And the system is designed to give no flexibility, in general:

Suddenly I have a lot more money and a lot less time, which means I have a lot more in common with the typical working North American than I did a few months ago. While I was abroad I wouldn’t have thought twice about spending the day wandering through a national park or reading my book on the beach for a few hours. Now that kind of stuff feels like it’s out of the question. Doing either one would take most of one of my precious weekend days!

The last thing I want to do when I get home from work is exercise. It’s also the last thing I want to do after dinner or before bed or as soon as I wake, and that’s really all the time I have on a weekday.

This seems like a problem with a simple answer: work less so I’d have more free time. I’ve already proven to myself that I can live a fulfilling lifestyle with less than I make right now. Unfortunately, this is close to impossible in my industry, and most others. You work 40-plus hours or you work zero. My clients and contractors are all firmly entrenched in the standard-workday culture, so it isn’t practical to ask them not to ask anything of me after 1pm, even if I could convince my employer not to.

| David Cain, Your Lifestyle Has Already Been Designed