10 Work Skills for the Postnormal Era

The World Economic Forum offers a list that's five -- or ten! -- years out of date.

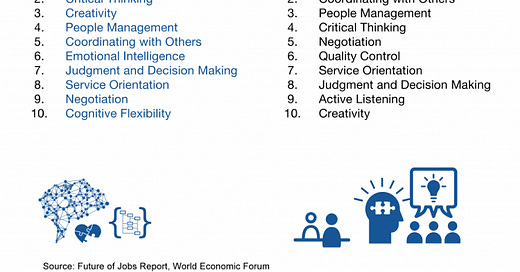

Dion Hinchcliffe tweeted out a graphic (not exactly the one below, but essentially the same) listing skills for 2020 in contrast to 2015 offered up by the World Economic Forum. He got me to thinking.

I think the World Economic Forum (WEF) — or their contributors on the report, Till Alexander Leopold, Vesselina Ratcheva, and Saadia Zahidi — are at least five years out of date. I think the set of skills they list for 2020 are the sort that CEOs and HR staff would have picked for new hires in 2010, or even 2005. I don’t hear the future calling in this list.

Here’s my table of skills, which also serves as a TL;DR if you are in a hurry:

First of all, let’s state explicitly that we’re talking about skills that are helpful for operating in the wildly changing world of work, and note that I make no distinction between the skills needed by management versus staff. That is an increasingly unhelpful distinction, as the skill set will make clearer, perhaps.

Here are some alternatives to those listed by WEF, which we’ll call postnormal skills. With the exception of Boundless Curiosity, they aren’t ordered by importance, although I bet for different domains they could be weighted profitably.

Also note that I left out a bunch of skills that are still relevant, like reading and writing and ‘rithmetic, as did the WEF researchers. But I am also dropping skills like coordinating with others, emotional intelligence, and complex problem solving. Because d’uh. Also missing are givens like virtual collaboration, new literacy, and participatory engagement. Again, these are today’s skills, since 2005 at least, or have the uncharming characteristic of being so commonplace that everyone thinks they know what they mean, even if they don’t. So, let’s at least plow some more fertile fields, shall we?

Here’s my ten-pack:

1. Boundless Curiosity

The most creative people are insatiably curious. They want to know what works and why.

In a world that is constantly in flux, dominated by a cascade of technological, sociological, and economic change, the temptation may be to shut our eyes and close our ears. However, the appropriate response is to remain flexible, adaptable, and responsive: and the only hope for that is a boundless curiosity.

Our educational system and business culture work hard to ‘suppress our natural tendency to be curious’, as Jamie Notter said. Messing around beyond the frontiers of the conventional can lead to dangerous ideas, which are generally stamped out as quickly as possible.

As I wrote a few years ago,

Curiosity occurs in the absence of extrinsic rewards, and people vary greatly in their degree of curiosity, or their responses to events and contexts that spur curiosity. It’s built into our brains, where we are rewarded for being curious with dopamine, the Kim Kardashian of neurotransmitters.

I believe that the most creative people are insatiably curious. They ask endless questions, they experiment and note the results of their experiments, both subjectively and interpersonally. They keep notes of ideas, sketches, and quotes. They take pictures of objects that catch their eye. They correspond with other curious people, and exchange thoughts and arguments. They want to know what works and why.

Curiosity is in fact the number one thing that Google now searches for in job candidates, now that they’ve junked the ‘how many ping-pong balls fit in a school bus’ nonsense. Laszlo Bock, Google’s head of People Operations, was interviewed on the topic:

For every job, though, the №1 thing we look for is general cognitive ability, and it’s not I.Q. It’s learning ability. It’s the ability to process on the fly. It’s the ability to pull together disparate bits of information. We assess that using structured behavioral interviews that we validate to make sure they’re predictive.

See longer discussion at Work skills for the future: Curiosity.

2. Freestyling

We have to learn to dance with the robots, not to run away. However, we still need to make sure that AI is limited enough that it will still be dance-withable, and not not-runnable-away-from.

As AIs and robots are expanding their toehold outside the factory floor, we are all going to have to learn how to play nice with them. Or, maybe said better, to use them to augment our work.

Tyler Cohen is the source of this skill (see Work skills for the future: Freestyling, for a deeper discussion). As he points out,

When humans team up with computers to play chess, the humans who do best are not necessarily the strongest players. They’re the ones who are modest, and who know when to listen to the computer. Often, what the human adds is knowledge of when the computer needs to look more deeply. If you’re a really good freestyle player, you consult a bunch of different programs, which have different properties, and you analyze the game position on all of them. You try to spot, very quickly, where the programs disagree, and you tell them to look more deeply there. They may disagree along a number of lines, and then you have to make some judgments. That’s hard — but the good humans do that better than computers do. Even very strong computers don’t have that meta-rational sense of when things are ambiguous. Today, the human-plus-machine teams are better than machines by themselves. It shows how there may always be room for a human element.

I really like that meta-rational thing.

We have to learn to dance with the robots, not to run away. However, we still need to make sure that AI is limited enough that it will still be dance-withable, and not not-runnable-away-from.

3. Emergent Leadership

Emergent leadership: the ability to steer things in the right direction without the authority to do so, through social competence.

Returning to Laszlo Bock’s interview, he said that Google’s second criterion for hiring is emergent leadership:

Traditional leadership is, were you president of the chess club? Were you vice president of sales? How quickly did you get there? We don’t care. What we care about is, when faced with a problem and you’re a member of a team, do you, at the appropriate time, step in and lead. And just as critically, do you step back and stop leading, do you let someone else? Because what’s critical to be an effective leader in this environment is you have to be willing to relinquish power.

As I wrote around the time of the interview,

The second most critical skill is … emergent leadership. Not the title, not a degree in management. But the ability to steer things in the right direction without the authority to do so, through social competence.

4. Constructive Uncertainty

The idea of constructive uncertainty is not predicated on eliminating our biases: they are as built into our minds as deeply as language and lust.

We’ve learned a great deal in recent years about human cognitive bias. Most important is to realize that we can’t counter our biases simply by becoming aware of them, anymore than you can correct your vision by understanding how the lenses in your shortsighted eyes are flawed. So we have to accept at a fundamental level that we are inherently wired to be biased, and therefore we need to systematically resist the peculiar gravity of bias.

That skill is what Howard Ross calls constructive uncertainty:

It is helpful to begin to practice what I call constructive uncertainty. Learning to slow down decision-making, especially when it affects other people, can help reduce the impact of bias. This can be particularly important when we are in circumstances that make us feel awkward or uncomfortable.

I wrote a few years ago about Ross’ idea, saying

In effect, Ross is suggesting that we slow down so that our preference and social biases don’t take over, because we are deferring decision making, and are instead gathering information. We may even go so far as to intentionally dissent with the perspectives and observations that we would normally make, but surfacing them in our thinking, not letting them just happen to us.

The idea of constructive uncertainty is not predicated on eliminating our biases: they are as built into our minds as deeply as language and lust. On the contrary, constructive uncertainty is based on the notion that we are confronted with the need to make decisions based on incomplete information. More than ever before, learning trumps ‘knowing’, since we are learning from the cognitive scientists that a lot of what we ‘know’ isn’t so: it’s just biased decision-making acting like a short circuit, and blocking real learning from taking place.

5. Complex Ethics

All thinking touches on our sense of morality and justice. Knowledge is justified belief, so our perspective of the world and our place in it is rooted in our ethical system, whether examined or not.

We are too quick to relegate ethics to the philosophers, off in ivory towers, and to leave ethics unexamined when discussing work skills. This actually means we are afraid to examine our ethics, because they are deeply buried, and strongly linked to our sense of self, identity and belonging. And deeply contradictory.

All thinking touches on our sense of morality and justice. Knowledge is justified belief (with apologies to Kant), so our perspective of the world and our place in it is rooted in our ethical system, whether examined or not. So, better to examine it, I think, if we are to break out of the futurelessness of our era, and overcome postmodernist solipsism and ennui.

As I wrote a few years ago,

The decline in faith, the break in identification with trusted organizations (government, religion, unions, nationalism), and the apparent collapse of the social contract all contribute to what I call postnormal traumatic stress syndrome: we are stressed beyond the breaking point by the postnormal world, but it’s not in the past. We are not past that stress: it’s an on-going state; permanent, and seemingly inescapable.

Complex ethics are needed to jumpstart ourselves and to consciously embrace pragmatic ethical tools. As one example, Von Foerster’s Empirical Imperative states we should ‘act always to increase the number of choices’.

But at this juncture, and in this post, let me simply say that simplistic ethical systems — like the current orthodoxy of the American Republican party: everyone for themselves — will have to be rejected, and complex ethical systems will have to displace them. For example, the premises that underlie the theory of the Commons as a foundation for political order (in both the geopolitical and workplace contexts) are likely to form a key element of any workable ethics for the future. And understanding the issues at play, and the tradeoffs involved, is a key skill for the future.

6. Deep Generalists

Deep generalists can ferret out the connections that build the complexity into complex systems, and grasp their interplay.

Jamais Cascio starts with evolutionary biology to examine what strategies will help us as we move out of the normal into the postnormal, a time of wild and violent volatility, where the normal ebb and flow of stable/unstable/stable/… isn’t in force. We’re in a period of unstable instability, and all bets are off. The postnormal.

Interviewed in the context of RU Sirius’ Prevail project, which is based on the optimistic goal of humanity prevailing, Cascio offered this

Near future work for Prevail movements (as there will be multiple versions, I suspect) will probably focus on getting broad expertise, becoming deep generalists. Learning a lot about a lot of things, and — just as important — getting a real understanding of how they are connected. I use both “deep” and “generalist” intentionally. The Prevail scenario is intrinsically adaptive, but what nature shows us is that the species that adapt best to radically changing environments are the generalists. But most generalists are shallow, living on the peripheries of more specialized ecosystems.

So we have to adopt the winning strategies of the two classes of living things: those that are specialists, deeply connected to the context in which they live, and at the same time generalists, able to thrive in many contexts.

We can’t be defined just by what we know already, what we have already learned. We need a deep intellectual and emotional resilience if we are to survive in a time of unstable instability. And deep generalists can ferret out the connections that build the complexity into complex systems, and grasp their interplay.

7. Design Logic

It’s not only about imagining things we desire, but also undesirable things — cautionary tales that highlight what might happen if we carelessly introduce new technologies into society.

I’m thinking not just about designing as envisioned up to the present, which is about products and their application. Tony Dunne and Fiona Raby in Design for Debate motivate the shift of focus from application to implication:

This shift from thinking about applications to implications creates a need for new design roles, contexts and methods. It’s not only about designing for commercial, market-led contexts but also for broader societal ones. It’s not only about designing products that can be consumed and used today, but also imaginary ones that might exist in years to come. And, it’s not only about imagining things we desire, but also undesirable things — cautionary tales that highlight what might happen if we carelessly introduce new technologies into society.

So postnormal design logic jumps the curve from dreaming up things to build and sell, to using the logics of user experience, technological affordance, and the diffusion of innovations in a more general sense, in the sense of envisioning futures based on our present but with new tools, ideas, or cultural totems added, and being able to explore their implications.

8. Postnormal Creativity

In postnormal times creativity may paradoxically become normal: an everyone, everyday, everywhere process.

I’m forced to use an inartful adjective to wrench the sense of ‘creativity’ out of the context of its usage today. Alfonso Montuori sums this up by saying

Creativity was not quite ‘‘normal’’ in Modernity, if we are to believe the popular Romantic mythology of tortured geniuses and lightning bolts of inspiration. We should therefore expect that in postnormal times creativity will have a few surprises in store for us. In fact, creativity itself has changed, and in postnormal times creativity may paradoxically become normal in the sense that it will not be the province of lone tortured geniuses any longer (which it was not anyway), but an everyone, everyday, everywhere process.

Taking Montuori’s vision into the context of today’s and tomorrow’s world of business — and leaving the great, blanketing narratives of the postmodern behind — I’ll add one ‘petit recit’ (or little narrative, a la Lyotard): we live in a time where innovation is the foundation of business. We will need to educate ourselves in the pragmatics of how innovations move from dream to ‘dent’, from a lightbulb-in-a-thought-balloon to a world-altering contraption or concept.

9. Posterity, not History, nor the Future

While we need to learn from history, we must not be constrained by it, especially in a time where much of what is going on is unprecedented.

George Santayana famously said,

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

However, while we need to learn from history, we must not be constrained by it, especially in a time when much of what is going on is unprecedented.

Rather than learning the list of US Presidents, or who won the Battle of Thermopylae (everyone’s seen 300, right?), we should instead cultivate the skills that come from reflecting on posterity, the future generations, and the world we will leave them. ‘Posterity’ implies continuity of society and the obligations of those living now to future inheritors, a living commitment, while ‘the future’ is a distant land peopled by strangers to whom we have no ties.

Kenneth Boulding, the thinker who coined the expression Spaceship Earth, wrote in 1966,

Why should we not maximize the welfare of this generation at the cost of posterity? “Après nous, le déluge” has been the motto of not insignificant numbers of human societies. The only answer to this, as far as I can see, is to point out that the welfare of the individual depends on the extent to which he can identify himself with others, and that the most satisfactory individual identity is that which identifies not only with a community in space but also with a community extending over time from the past into the future. If this kind of identity is recognized as desirable, then posterity has a voice, even if it does not have a vote; and in a sense, if its voice can influence votes, it has votes too.

This is a part of the new ethics we need, but also the skills of futures work: to actively imagine and ‘design’ futures, and to consider them in the light of the people who will inhabit them. As I wrote last year,

We need to colonize the future ourselves, we must make our own maps of that territory, maps that show us as inhabitants and inheritors, making new economics, breaking with the deals and disasters of the past, and committing again to each other: to be a community and not consumers, to be partners and not competitors, to be from the future and beyond the past.

Maybe I should call myself a posterity-ist instead of futurist?

10. Sense-Making

Skills that help us create unique insights critical to decision making.

I’ve lifted this skill from a 2011 report from The Institute for the Future (Future Skills 2020): Sense-Making.

definition: ability to determine the deeper meaning or significance of what is being expressed

As the authors said,

As smart machines take over rote, routine manufacturing and services jobs, there will be an increasing demand for the kinds of skills machines are not good at. These are higher-level thinking skills that cannot be codified. We call these sense-making skills, skills that help us create unique insights critical to decision making.

Or twisted around a bit, we need to nurture the ability to create flexible models to derive meaning from a set of information, events, or the output of our AIs, and determine a course of action.

I was tempted to stop at nine skills, and end with an empty 10. Just have ten in this list so I can have the number ‘10’ in the title, but I actually did find ten that are solid, I think.

I offer these with this coda: I don’t think these skills are being taught, generally, or at least not in any sort of systematic way. At some point, the inevitability of these skills may change that. There’s a small cadre of agitators (I include myself) shouting out that the times are a-changin’, but I don’t know how far our voices carry, or if others can understand our words.

I’m reminded again of TS Eliot’s Little Gidding:

For last year’s words belong to last year’s language.

And next year’s words await another voice.

Perhaps this is proof, once again that we need new ways to think about — and talk about — this rapidly changing world: we will have to find another voice.

Maybe that’s the eleventh skill.