In Times of Dread

Toni Morrison | Debiasing Strategic Decisions | Factoids | Elsewhere, Elsewhen

This is precisely the time when artists go to work—not when everything is fine, but in times of dread. That’s our job.

| Toni Morrison, No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear

Debiasing Strategic Decisions - Part 1

[An excerpt from a ‘booklet’ I am working on, On Decision-Making. A booklet is to a book as a novella is to a novel. Some of these materials were originally published on the Sunsama blog.]

…

If Decision-Making Is So Important, Why Do We Take Shortcuts?

Decision-making is critical to business performance. To go even further, it is an existential requirement. Yet so often things go wrong. Why?

Some problems in strategic decision-making seem obvious when you step back far enough. Consider the 'loss aversion' problem. Operating unit managers are focused on short-term timeframes, and therefore tend to take on only small risks, instead of larger ones that may contribute more to long-term corporate growth. They are more concerned with the possibility of a decrease in status if things go wrong: the potential loss for the manager may be perceived as worse than any potential upside for the company and the manager.

Senior managers, however, must take a portfolio view and therefore must anticipate a portion of projects to fail in the search for a few that will yield big returns. The incentives — and fear of downside risk — between corporate goals and the individual manager’s goals are mismatched.

The important takeaway is this: the economic downside of loss aversion is only one instance of a much larger case of cognitive biases that distort human behavior whenever decision-making is called for. And like so many other aspects of life, avoiding examination of these influences on our behavior leads to big problems.

The basic assumption is wrong.

The basic assumption in business is that strategic decision-making requires three basic elements:

fact-gathering and analysis,

the insights and judgment of a defined group of people (stakeholders or advisors), and

some process -- ranging between very formal to very informal -- for that group to make a decision, reflecting that analysis and judgment.

However, as Dan Lovallo and Olivier Sibony reveal,

Our research indicates that, contrary to what one might assume, good analysis in the hands of managers who have good judgment won’t naturally yield good decisions

And why is that? The authors go on to draw our attention to the third part: the process. After extensive analysis of 1,048 major decisions over a five-year period, including investments in new products, M&A decisions, and large capital expenditures they determined that

process mattered more than analysis—by a factor of six.

Process, by extension, is also more valuable than the judgment of those involved in the decision-making, too, since flaws in both analysis and judgment are countered by processes designed to do exactly that.

Process, process, process.

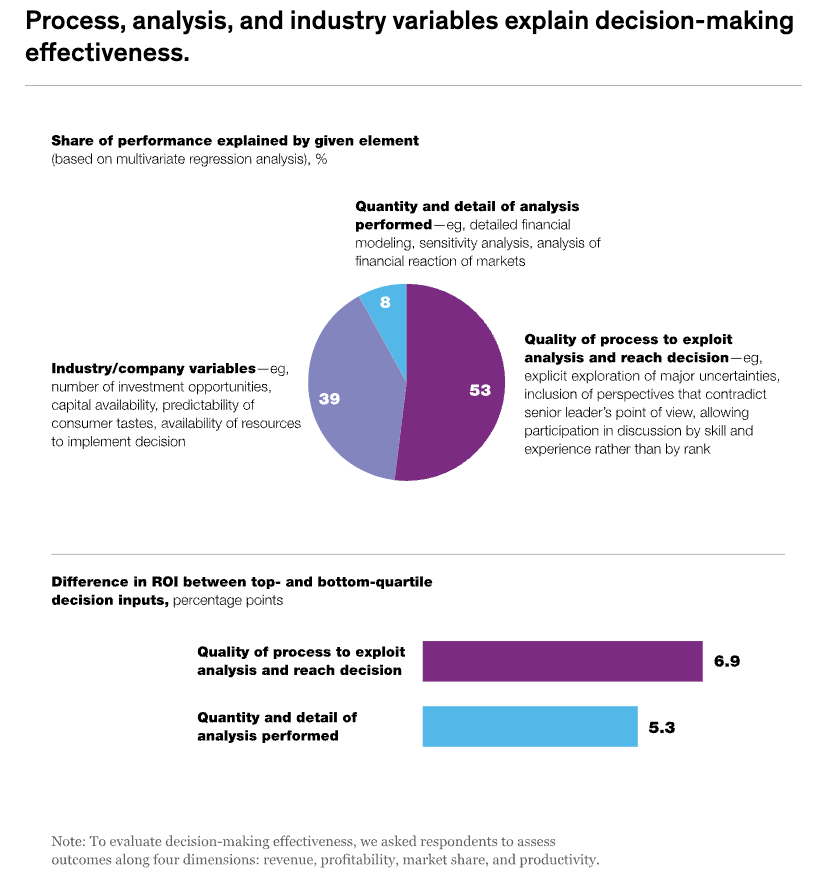

Lovallo and Sibony took a hard look at decision-making effectives, and broke things down:

And a major value of good decision-making processes are to overcome — or at least moderate — cognitive biases that lead to poor decisions. As Lovallo and Sibony put it:

The prevalence of biases in corporate decisions is partly a function of habit, training, executive selection, and corporate culture. But most fundamentally, biases are pervasive because they are a product of human nature—hardwired and highly resistant to feedback, however brutal. For example, drivers laid up in hospitals for traffic accidents they themselves caused overestimate their driving abilities just as much as the rest of us do.

Improving strategic decision making therefore requires not only trying to limit our own (and others’) biases but also orchestrating a decision-making process that will confront different biases and limit their impact. To use a judicial analogy, we cannot trust the judges or the jurors to be infallible; they are, after all, human. But as citizens, we can expect verdicts to be rendered by juries and trials to follow the rules of due process. It is through teamwork, and the process that organizes it, that we seek a high-quality outcome.

In the next issue of Work Futures, I will explore the most common biases that bedevil decision-making in the corporate context, and approaches to sidestep some of their worst effects.

Factoids

Head in the clouds.

Revenue from cloud businesses at Amazon, Microsoft and Google reached a total of $62.9 billion last quarter. That figure is up 22.2% from the same period last year and marks at least the fourth straight quarter in which their combined growth rate has increased.

…

Standing won’t fix sitting. Walking helps, though.

A large new study of more than 83,000 adults found that standing for more than two hours a day — as many people with standing desks do — didn’t protect against the cardiovascular risks of too much sitting.

Those hours of standing also turned out to have their own downsides, increasing people’s likelihood of developing serious circulatory problems, including varicose veins, abnormally low blood pressure and blood clots, compared with people who rarely stood.

I tried a standing desk a few years ago and it made my feet hurt. Nowadays, I try to go for a walk three or four times a day, with a target of 7,500 steps.

…

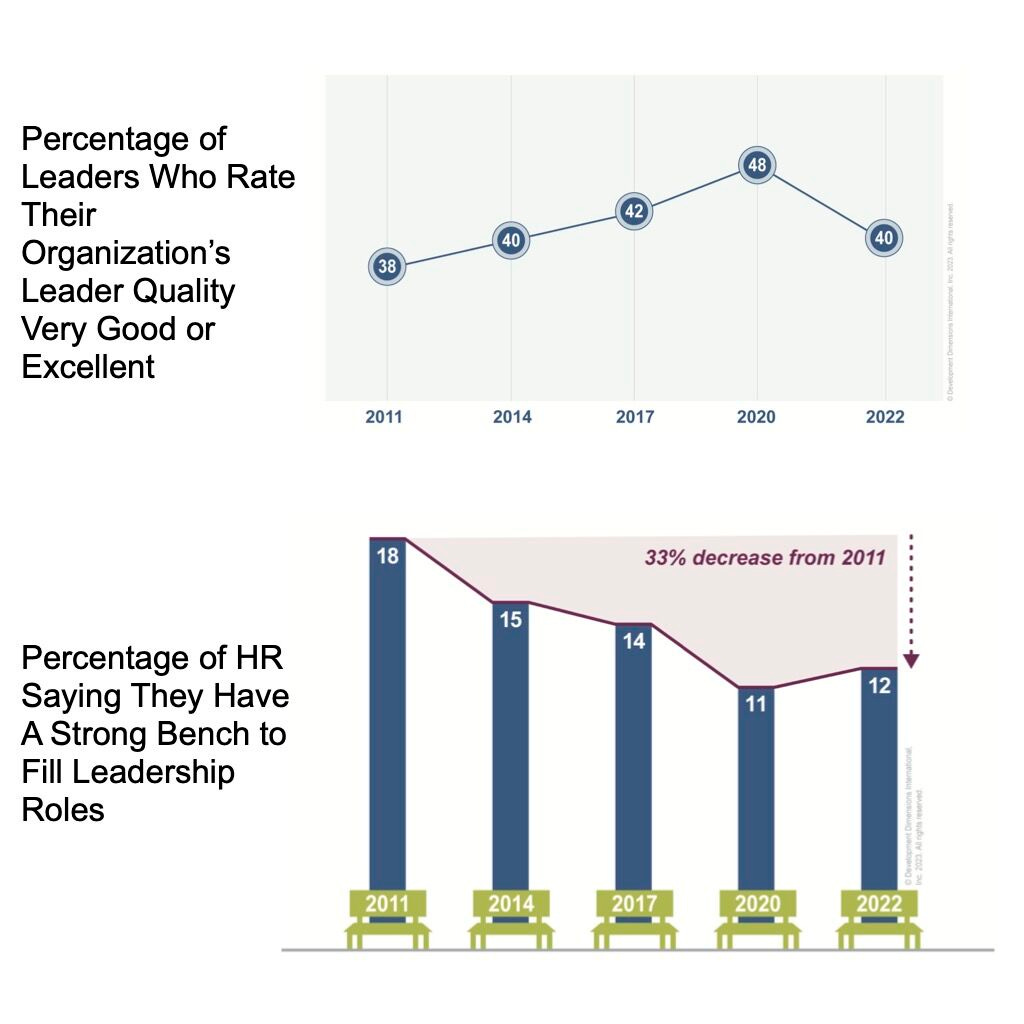

What Do You Get From $50B in Executive Training?

Not much.

I read a LinkedIn post by the endlessly informative Michele Zanini:

Honest question: What corporate expense has worse ROI than leadership development? $50B+ spent annually on executive training, yet the outcomes are bad and getting worse.

source: DDI | Development Dimensions International Global Leadership Forecast Survey, 2023

Whoops. It’s bad and getting worse.

Elsewhere

The ‘old boy’s club’ hasn’t been disbanded, they are just lurking in the shadows.

In Sexism in the City: ‘No matter how hard I work, they will never ever recognise me’, Kalyeena Makortoff writes about an inquiry by the UK House of Commons leading to a report, 'Sexism in the City':

Prompted in part by the sexual harassment allegations against hedge fund boss Crispin Odey, the inquiry is meant to determine whether meaningful progress had been made since the committee’s last review in 2018. But the shocking stories recently shared with MPs for its investigation – which ranged from office bullying to allegations as serious as rape – suggest the post-#MeToo focus on diversity and inclusion has failed to eradicate widespread misogyny.

Instead, the “old boys’ club”, according to the committee’s interim report, has been pushed into the shadows. Sexual harassment may be less prevalent in the office, but is more often taking place at conferences and work trips, while bad behaviour has merely become “more underhand and pernicious”, the committee explained.

I am unsurprised.

Elsewhen

It pays to be thin, especially for women.

In The economics of thinness, The Economist (2022) lays out an economic analysis of the payoffs from being thin:

Regarding the payoffs:

Research in America, Britain, Canada and Denmark suggests that overweight women do have lower salaries. The penalty for an obese woman is significant, costing her about 10% of her income.

And, ‘this may be because the increasing rarity of thinness has led to its rising premium’.

In the final analysis,

It is economically rational for everyone to devote time to education because it has clear returns in the labour market and for future wages. In the same way it appears to be economically rational for women to pursue being thin. Obsessing over what and how much to eat and paying for fancy exercise classes are investments that will bear returns. For men they are not.

The Economist quotes Jia Tolentino, who in Trick Mirror writes, Feminism ‘has not eradicated the tyranny of the ideal woman but, rather, has entrenched it and made it trickier’.

And skinnier.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work Futures to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.