Without Reflection

Margaret Wheatley | Personality Hire | Economists Were Wrong | The Great Compression | Factoids | Constructive Uncertainty

Quote of the Moment

Without reflection, we go blindly on our way, creating more unintended consequences, and failing to achieve anything useful.

| Margaret Wheatley

Meme of the Moment: Personality Hire

I follow Cloey Callahan pretty closely. She’s closer to some aspects of work-cultural phenomena than I am. She wrote about a term I hadn’t encountered:

Some people would describe a

personality hireas someone who excels in boosting company culture and navigating interpersonal dynamics, while others would consider them slackers who compensate for their lack of skills by bringing good energy to the workplace, thereby boosting culture.And rather than be sheepish about how they might have been hired predominantly for their personality, rather than their ability to excel in a role, they’re OK with it — with some even celebrating it online.

That’s new.

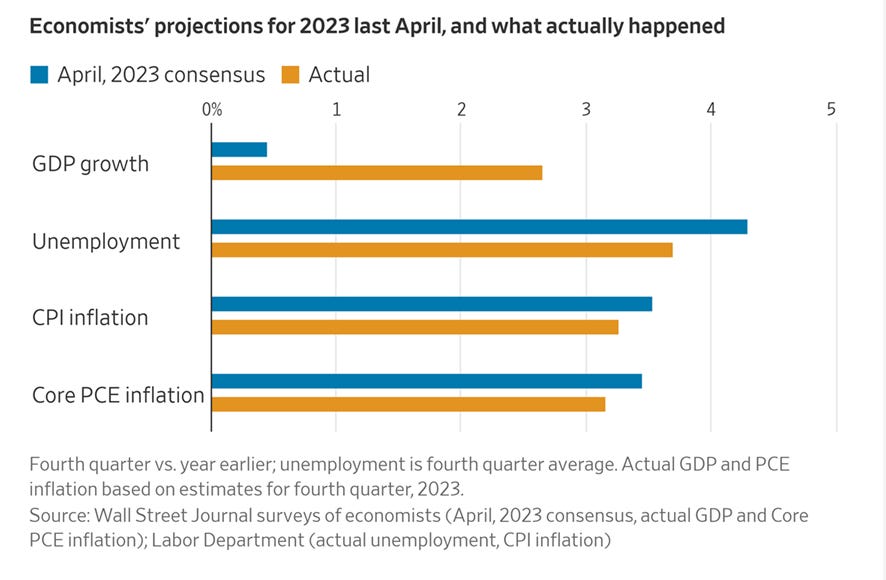

Economists Were Wrong

There’s been a great deal written about how off-base economists were about GDP, inflation, unemployment, and other economic indicators. Mohamed El-Erian tweeted this today. Note that El-Erian predicted a recession in November 2022.

They were prepared for a recession, which is strangely not on the chart, directly.

The Great Compression

Some economists, however, were right about the economy. Paul Krugman wrote this week about The Great Compression — research by David Autor, Arindrajit Dube, and Annie McGrew — some extracts:

Whenever I write about the good economic news of 2023, our remarkable success in sharply reducing inflation without a surge in unemployment, I get two kinds of pushback. Most of that pushback comes from Republicans, three-quarters of whom say that it was a bad or terrible year for the country, even though almost 70 percent of them say that it was OK or better for them personally. But I also get pushback from some on the left, who insist that our so-called recovery helped only the rich and did nothing for ordinary families.

This is completely wrong.

The post-Covid economic recovery has produced especially large wage gains at the lower portion of the scale, compressing the wage distribution.

Wages in America are still highly unequal but not as unequal as they were just a few years ago. In fact, they found, we’ve reversed almost 40 percent of the rise in one key measure of inequality that took place during the great income divergence from 1979 to 2019.

Why did wage inequality fall? A number of states increased their minimum wages. Unions won some victories, and fear of unionization may have pushed some employers to increase pay. The main factor, however, was surely a tight labor market: Full employment greatly increases workers’ bargaining power.

Full employment also did wonders for another aspect of racial disparities: high Black unemployment. Last hired, first fired is still a very real fact of race relations in America; one measure of our success in finally achieving something like full employment is that the gap between Black and white unemployment rates is the smallest it has been since the government started collecting data on the subject.

It’s now clear that the deficit obsession of the 2010s, which delayed recovery from the 2007-9 recession for many years, was a social as well as economic tragedy. And we’re at risk of a similar tragedy if the Federal Reserve lets itself be bullied into keeping interest rates high by Republicans accusing it of cutting rates to help President Biden — not, you know, because the inflation that caused it to raise rates has subsided.

Factoids

In November some 42% of car sales in China were either pure battery or hybrids. That is well ahead of both the EU, at 25% or so, and America, at just 10%. What is more, although the pace is slowing, Chinese EV sales are still growing fast: by 28% in the third quarter of 2023 compared with a year earlier, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers. Most forecasters reckon that by 2030 some 80-90% of cars sold in China will be EVs. And China is now by far the biggest car market in the world, with about 22m passenger vehicles sold in 2022, compared with less than 13m in both America and Europe. | Economist

…

Forty-three percent of our 4.2 million miles of road, meanwhile, are in poor or mediocre condition. And they’re unlikely to be repaired soon, given the $786 billion construction backlog. | American Society of Civil Engineers

…

Neuromodulator injection, which includes the use of Botox, was up a staggering 73 percent in 2022 compared with 2019. | Jessica Grose

Ageism is driving many to de-age their faces.

Constructive Uncertainty

The world is complex, and we must find a balance between taking action and accepting uncertainty. Our natural impulse toward quick decisions misses out on a powerful tool: negative planning.

…

One of the paradoxes that reveals a great deal about making sense of the world is the tension between uncertainty and action. On one hand, we are often told that being effective relies on decisive reasoning, and quickly choosing a course to pursue even with incomplete information. However, opting to eliminate the discomfort of an uncertain or ambiguous situation by making a quick decision can often backfire, and in predictable ways.

When I recall events in my life where my decisions went sideways, they were often hurried, and driven more by my desire to end a period of stress and insecurity than actually determining what could go wrong… before finding out the hard way.

And the world is more complex that ever, more ambiguous, less predictable. As Margaret Wheatley points out in Willing to Be Disturbed, "We live in a complex world, we often don’t know what’s going on, and we won’t be able to understand its complexity unless we spend more time in not knowing."

Wheatley's formulation, that we need to spend more time in not knowing, is a first step in deconstructing uncertainty. One aspect of contemporary emotional maturity is to accept the state of not knowing. Not having a quick answer for complex questions. Being willing to admit being confused by new situations, or rapid changes in the context we are living and working in. Remaining open to spending more time listening to alternative viewpoints before shutting down gathering inputs. These are all aspects of constructive uncertainty, a term I learned from Howard Ross: "Learning to slow down decision-making".

The poet John Keats commented in a letter to his brothers that Shakespeare was able to accept uncertainty in his characters and their context, and coining the term negative capability to capture what he described as "being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason".

So, too, we need to cultivate a negative capability in our approach to an uncertain world. All too often we approach decision making or strategy formulation in an overly positive manner, which may have serious downsides. JP Castlin argues that "instead of explicitly stating what one might do, and thereby implicitly what one might not do, one does the opposite (explicitly stating what one might not do, and implicitly what one might do)." He believes this leads to a more open-minded approach, spending more time in Wheatley's not-knowing, and avoiding the pitfall of closing off Keat's uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Work Futures to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.