A Useful Fiction

Marcus Buckingham, Ashley Goodall | Cultural Incoherence | Factoids | BANI

Quote of the Moment

Just as the idea of the company is […] unreal, so is the idea of company ‘culture’. It’s a useful fiction. That doesn’t mean we should dispense with it; however, that does mean we should be careful not to mistake it for what it isn’t. Culture locates us in the world. It consists of stories we share with one another to breathe life into the empty vessel of “company.” But—and here’s the kicker—so powerful is our need for story, our need for communal sense making of the world, that we imagine that our company and its culture can explain our experience of work. And yet it can’t. So strong is our identification with our tribe that it is hard for us to imagine that other people inside our company are having a completely different experience of ‘tribe’ from us. Yet they are — and these local team experiences have far more bearing on whether we stay in the tribe or leave it than do our tribal stories. | Marcus Buckingham, Ashley Goodall, Nine Lies About Work

Cultural Incoherence

Buckingham and Goodall uncovered a subversive insight. When companies prate about their unique culture it’s an effort to take a shared fiction and use it to spin a story for workers, current or prospective. It’s a form of propaganda.

The authors make the case for team culture as the defining reality of work for the great majority of people. It’s how you interact with your immediate set of coworkers (think daily interactions), and, to a lesser extent, a slightly larger group (think weekly interactions). That’s the lived experience for most people.

The fiction of an amorphous, heterogenous company culture may be at odds with someone’s tribal experience, and may, in some pathological cases, not align with any tribal cultures in the company, at all, like a Venn diagram with only a tiny area of overlap between ten thousand circles.

Nonetheless, much of the chatter about company culture misses the Buckingham-Goodall insight, and sets about attempting to shape a mass ‘company culture’ with certain attributes, without ever acknowledging the myriad tribal cultures people live in. and through which they experience work.

I noticed this in a report from PWC that surveyed people across a totally different gradient, dividing the responses from leaders and employees across 45,127 respondents from an untold number of companies. How can such a survey tell you anything about company culture, unless you extend the notion of mass culture to the most extreme interpretation: that all companies are homogenous?

I’ll zoom into one section of the report, Uniting a divided workforce, one that focuses on culture.

Gap 3: Defensive culture

CEOs worry about company culture. Employees say it’s worse than they think.

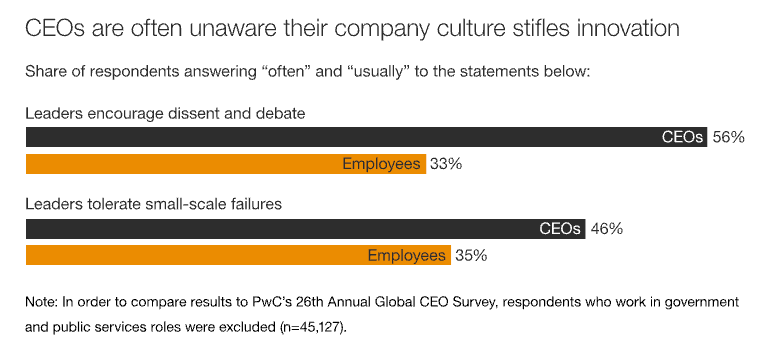

Experimenting, proposing new ideas, offering dissenting opinions—from the perspective of senior leaders, these are hallmarks of innovation. Yet, only about half of CEOs say their company leaders tolerate small-scale failures or encourage dissent and debate. Worse, just one-third of employees agree.

It’s not easy for employees to contradict a more senior team member or admit failure—especially if they fear reprisal. And this dynamic is even more challenging when they struggle with feeling included or accepted within a company—only half of employees in the Hopes and Fears survey said they can truly be themselves at work. If you have any transformative plans for your company, this particular gap should be a red flag. As PwC’s Katzenbach Center notes, differences between what leaders say about their company’s culture and what employees actually experience can cause a sense of “cultural incoherence” that erodes trust—making it much more difficult to enact change.

CEOs are often unaware their company stifles innovation

How are we to interpret this? There is a gap between what CEOs think and everybody else thinks. But this isn’t about culture at work: these people don’t all work together. It’s hundreds or thousands of companies. What this reveals is something more like a class distinction: the managerial class and the rank-and-file have a serious difference in their work experience. As PwC styles it, this is a sign of cultural incoherence across the world of business, and one which may reflect the world generally. But it is not a match with the situation inside of any specific company.

Don’t get me wrong, I am all for CEOs trying to ‘bridge the gap’ with people in their companies, but — as Buckingham and Goodall detail in Nine Lies — you can only get there through the hard work of asking each group or team to share their specific shared experience, instead of averaging everything flat. The law of large numbers just leads to a reversion to the mean, but no one may live that experience, at all.

Factoids

Global demand has pushed cubicles and partitions to a $6.3 billion market, which is expected to grow over the next five years to $8.3 billion, according to a 2022 report from Business Research Insights, a market analysis firm. | Ellen Rosen

The ‘quiet revolution’ is on the rise as people return to the office, but want the privacy and quiet they came to enjoy working from home. Ergo, the return of the cubicle.

…

The internal messaging app Slack alone boasts 300,000 messages sent per second, and 145 million people log onto Microsoft Teams for similar discussions each day. | Melissa Swift

…

Globally, the top 10% of [carbon] emitters were responsible for almost half of global energy-related CO2 emissions in 2021, compared with a mere 0.2% for the bottom 10%. The top 10% averaged 22 tonnes of CO2 per capita in 2021, over 200 times more than the average for the bottom 10%. There are 782 million people in the top 10% of emitters, extending well beyond traditional ideas of the super rich. | IEA

We should make these people — or their organizations — pay for this pollution.

BANI

In BANI and Chaos, Jamais Cascio argues that the VUCA model of thinking about the world (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) is obsolete: 'declaring a situation or a system to be volatile or ambiguous tells us nothing new' when everything is. The replacement he suggests is BANI: ' Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, and Incomprehensible — is a framework to articulate the increasingly commonplace situations in which simple volatility or complexity are insufficient lenses through which to understand what’s taking place.'

'At least at a surface level, the components of the acronym might even hint at opportunities for response: brittleness could be met by resilience and slack; anxiety can be eased by empathy and mindfulness; nonlinearity would need context and flexibility; incomprehensibility asks for transparency and intuition.' 'BANI makes the statement that what we’re seeing isn’t a temporary aberration, it’s a new phase.'

In either case -- reactions or solutions -- these need to be expanded on.

This brings this line to mind: And next year's words await another voice. | T.S. Eliot]